“The world is not what you think it is.” Rod Dreher opens Living in Wonder with that line, one that can rattle the reader when it actually begins sinking in throughout the course of this book. I’ve struggled with writing this review because this is one of the stranger books I’ve read over the tenure of the blog: the struggle lies not in the strangeness but because I don’t know how to think about the strangeness. Dreher is a journalist and author whose books touch on Christianity and culture, and he’s been calling with increasing urgency for Christians to take their place in the world more seriously. Here, though, he looks beyond the temporal into the spiritual — to where we wrestle not with flesh and blood, but with “against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.” These are not factors most of the modern postwest thinks about: we are “material girls in a material world”, convinced that we are singular intelligences rising from dead matter and ruling over it, shaping the world to our will and actively trying to create a new intelligence out of bits of silicon and code. But what if that were not the case? Living in Wonder invites us to consider that there is a spiritual world beyond, that the west’s turning away from it has not lessened our hunger for it, and that certain trends in our current time are the result of people groping in darkness for that something else and finding trouble. This is a fascinating little volume that brings in hermits and saints, technologists and architects, all into a common conversation about the human need for enchantment. It is both an unusual look at modern society and a work of Christian formation, urging a deeper and richer religious practice — one that will sustain Christians against the adversity to come, from both ‘princes and powers.’

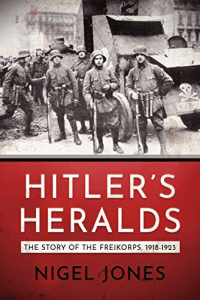

I should note from the start that I have an unusual relationship with this book: I’ve been following Rod’s substack long enough that I was ‘present’ for its entire life, from Rod announcing his next book idea, to his sharing interviews as he conducted them, even to voting on what book cover I thought was best. I’ve therefore been living with his thinking and his arguments for a lot longer than from when I acquired the book in October shortly before its release. Dreher begins by pointing out that the contemporary western world is an outlier in human history in its strict materialism, and he traces the rise of that materialism beginning in the medieval era, with the rejection of nominalism. Nomimalism asserted that the material world is inherently meaningless, save for that meaning which we humans assigned to it. It countered the medieval conviction that the material world was inherently saturated with meaning of its own, not simply what human thinking assigned to it: all of creation was endued with something else — immanent with the presence of God. This divorce of the world from its creator, and the driving out of the realm of spirit altogether, became larger and larger through the Protestant rupture and then the Industrial Revolution, the latter of which not only made it easier to believe only in the material world, but opened the door wide to profits and power. As Wendell Berry observed, there are no such things as unsacred places — only sacred and desecrated places. The trees have no dryads, no spirits, reflect no beauty of God: they are merely timber waiting to be harvest. The mountain has no glory, only minerals to mine. Families? What are they but cogs in the machine and then wallets to plunder? The twentieth century’s millions upon millions killed in grim industrial fashion shows what happens when the machine is set upon human beings who, after all, are not persons made in the image of God, but simply animals to be disposed of if they’re inconvenient to a political ideology, whether it be Nazism or the far more murderous state socialism of Stalin and Mao.

Despite the apparent triumph of materialism, people still appear to sense an absence, as though the house is missing a wall, or a roof. In The Enemies of Reason, Richard Dawkins mourned the fact that Europeans had gone from believing in God and saints right back to believing in fae folk and horoscopes: it’s as though we’re primed to believe in something else — or, as Lewis posited, “made for another world”. These days we are looking for the something else from other quarters, Dreher argues — from dabbling in the occult to psychedelics to UFOs. These are not unrelated, either: one book discussed here intimates that UFOs are not physical arrivals from another world, but rather manifestations of some other intelligence that is appearing in a form that we are prepared to accept. One man Dreher interviewed claimed that he saw a shimmering in his kitchen through which stepped two E.T.’s, who began predicting mundane events that would happen shortly: a bird landing on a sill, a car horn going off, etc. This man saw these visitors once a year for several years, and so did his wife. He sought answers from neurologists, who found nothing wrong with him: eventually an exorcism gave him relief from these beings, from whom he felt a strong sense of malice. Dreher also suspects that our experiments with AI may be acting like a high-tech ouiji board through which other beings are trying to insert themselves into, and quotes technologists who are gravely concerned about what they’re creating and yet feel compelled to summon it to life. More disturbing for me were the accounts from people who have taken DMT and report seeing similar beings in whatever plane their brain is going to while under the influence: Dreher thinks that somehow these drugs allow human consciousness to perceive the numinous more directly, but in a chaotic and dangerously exposed way. The threat from LSD and similar substances in not that they don’t do anything real, Dreher writes, but that they do.

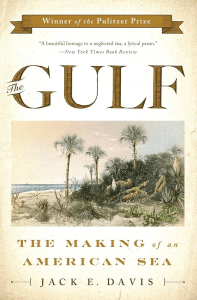

Of course, it’s not just baddies out there in the ether: Dreher also discusses miracles and mystic experiences, including his own, and these are part of the fundamental point of the book, which is not merely to argue that the spiritual realm exists, but that it must be taken seriously. Not only does becoming more porous to the enchanted realm enrich the Christian life, something which will be much more important as the world grows more hostile toward Christian faith, but spiritual warfare is happening regardless of whether we believe it or not, and if we’re going to walk through a battlefield it would behoove us to find shelter and return fire from time to time. (Or at the very least, don’t open doors into the spiritual realm when we don’t know what’s on the other side.) Dreher’s own story is a powerful testimony into what living in the “enchanted world” can do: in the last decade he has been drug through several layers of hell, with family drama, heartbreak, excruciating illness, and then divorce. Through this, it has been his Orthodox faith and the way it calls him above the material world, allowing him to see beauty in broken places, to find meaning in suffering and to help other ‘forlorn and shipwrecked brothers‘. One especially powerful story he has shared takes place across several years, as he recounted being confronted by an Italian artist at a book launch years ago, and presented with a hand-drawn portrait of a strange scene involving a saint, St. Galgano: this was first in a series of events about Galgano and the church named in his honor that drove Dreher to write this book, and has become an integral part of Dreher’s religious understanding. Dreher shares some of his practices for making himself more ‘porous’, more open to the voice of God, including the Jesus Prayer that I’m given to understand is a fundamental part of Orthodox prayer life. Another recommendation is dialing back immersion in the digital world: smarthphones, he writes, are disenchantment machines, destroying our ability to be mindful and present in the moment, or attend to anything — mired in the quicksand of push notifications and facebook reels.

This is an intense book. When Rod first started writing about this a couple of years ago, I remember thinking wow, he’s getting into some weird stuff, but the more he interviewed people the less absurd it seemed to be. Looking around the world today, I can almost believe in some being that actively hates a human race made in the image of God and wishes us ill: the increasing absence of beauty in western architecture and art, soaring rates of mental illness, the war on biological reality, plummeting birthrates, the black hole of egoism that both are connected to — the worship of greed and excess, the loathing so many sectors of the population have for each other, the pervasive lust for domination, the fact that politicians keep pushing us closer to nuclear war despite the fact that it means the destruction of a habitable Earth and the extinction of humanity, — I could go on. There’s a reason the closest thing I have to social media these days is goodreads. There is a small part of me that would readily believe that yes, Satan and all of hell are out to enslave humanity and are planning on using technology to do it — but I say that knowing my own deep-seated mistrust of the Machine. Then, too, is my own skepticism: after I escaped the Pentecostal sect I was raised in, I hardened my heart toward religion and the supernatural, and despite having a series of mystical experiences that drew me back to God and then to Christianity, I’ve retained that skepticism for the most part. Reading Dreher and other’s experiences with something beyond has rattled that a bit, even as part of my brain is arguing with their experiences. “Rod is a creative personality and has an increased ability to see patterns when they aren’t there,” “Rod is reporting what someone else reported to him, but how can we know if they’re legit?” “Rod took LSD once as a teenager, so who knows how changed his brain long term?” — that sort of thing. And yet it rattles me, and so did Will Storr’s Will Storr versus the Supernatural, because Storr himself experienced some weird stuff, and my impression when reading his book was that he was actively resisting admitting it, dismissing it all as quantum mechanics or whatever.

In short, I can’t give you a….thoroughly digested review for this book. I can only say it’s interesting as hell, it’s moving, and it’s unsettling. This is one I will revisit after the ladyfriend has finished it (I gave it to her to her just so I’d have someone to talk about the experience with), but I may buy the kindle version so I can have highlights. (The Selections posted yesterday were taken from photos I took of th book’s pages while reading!) There so much in the book this review is missing, simply because I want to get something out there, to get some of my thoughts onto the page so I can better organize my thinking.

Related:

If you want to learn more about Rod, WaPo did a story on him while he was researching the Benedict option book that goes into his biography a bit.