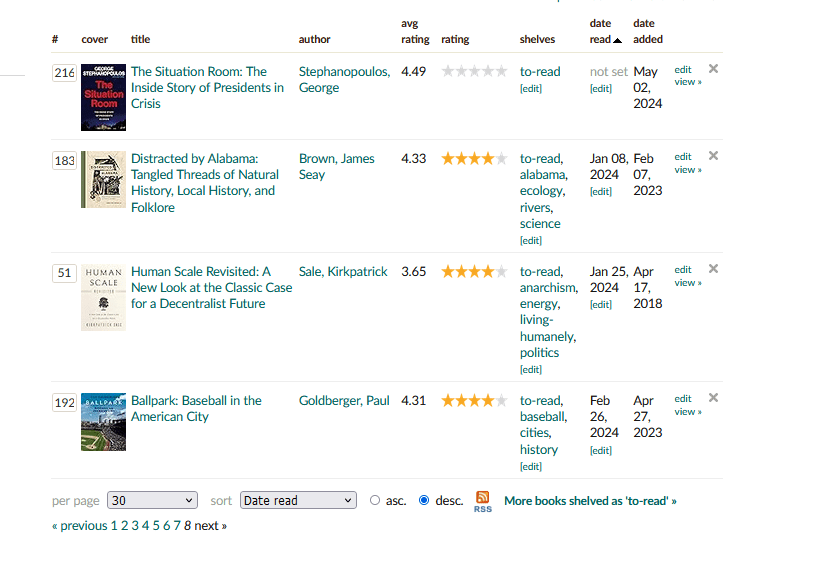

War. War never changes. Oh, the execution of it changes — spears become rifles, scouts on fast horses are replaced by drones and mining photos for GPS data — but the horror of it remains, as does certain truths like the difficulties inherent in asymmetrical warfare. China laughed at DC for virtually destroying itself in the Forever War, the mideast quagmire that consumed its men, material, and goodwill across the world for over twenty years — but now it’s created its own mess by invading the United States. Now it hasn’t even moved past the Rockies, and Los Angeles is the center of an insurgency draining China’s men and material away. Tiger Chair is a short story that takes the form of a letter written by a suicidal soldier who has been part of the invasion since the beginning — landing in the first wave, back before the Americans figured out how to disrupt the deadly drone swarms that killed so many of the defenders– who now believes the cause is lost. He desperately wants for the Party to acknowledge the facts and end this debacle before China repeats DC’s mistake and commits to a fool’s errand in which sons grow up to fight alongside their fathers. The war is already destroying its soldiers even of the battlefield, as demoralized they’re beginning soft mutinies by sabotaging their own equipment and injuring themselves to escape duty. Through the narrator’s mournful recollection of the war’s history, we explore different future military technologies, and how they are being thwarted by unpredictable means, generated by a creativity born of desperation. Some of these are uniquely tied to Los Angeles and the Hollywood background, with vocal training and prosthetics being used to frustrate social tracking and control mechanisms the Party is attempting to employ. Another element that Brooks explores is cultural differences and their consequences for occupation: the narrator is aghast at how ferociously Chinese-Americans are resisting their liberating brothers, finding their defiance both reprehensible and demoralizing, and addresses his frustration that the PLA’s heavy top-down control and overreliance on AI are preventing field officers from making creative snap decisions — and the Americans are using this to their advantage, using protocol against the invading army. Although this is a short piece (50 pages), I was fascinated by the tech being employed and thought the premise extremely interesting. It appears that a Party invasion of Taiwan turned into World War Three, with a general Asian front and some action in Africa as well. Brooks wrote World War Z. Available on KU.

Highlights:

Why can’t we learn from America’s mistakes? Americans have. They’ve used the blood of their fallen to write an entirely new rule book for warfare. And rule one is as old as Vietnam: simplicity can defeat technology.

We coerced the fickle Hollywood “in crowd” to turn their backs on their former hero, the Dalai Lama. We manipulated movies—and moviemakers—to portray us only in a positive light. I still think about my information operations course at Shijiazhuang, when Professor Tan showed us the 1984 movie Red Dawn and explained that, for the 2012 remake, the cowardly, moneygrubbing producers changed America’s new invaders from us to the North Koreans. I’ll never forget Tan’s words: “Our greatest weapon is their own greed.”

To follow doctrine is to spread the blame, but bucking it means owning the consequences. Can you see why no mid-grade or even senior officer has ever stood up to Jiang Ziya? Can you see why today turned out the way it did?

Our men are the greatest human beings our country has ever produced: smart, brave, and stronger than I’ll ever be. I let eight of them die today, and I don’t know how to help the survivors carry the loss.

Did our generation’s Deng attack Taiwan to distract us from the plague and recession and all the unrest they were causing? Is history repeating itself on two levels? Doesn’t our escalation into another world war mirror the beginning of the first one? A local spat that spun out of control? And didn’t that war stop only when soldiers turned on the leaders who started it?

Which serves our country more? Fighting its war, or fighting to stop it?