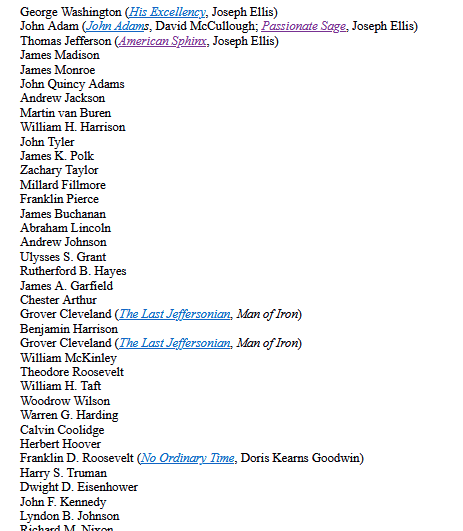

What do I know about Mr. James Buchanan? Well, he’s our only bachelor president, leaning on his niece to be his hostess at White House functions; he was very chummy with the founder of my hometown, William Rufus King, and supposedly when the South seceded he simply shrugged and said “Yeah, that’s an 1861 problem, not an 1860 problem.” Jean H. Baker argues that Buchanan was by no means passive; he was, in fact, quite an activist — but he acted in favor of his friends, with extreme partiality towards the South, and was so confident in his abilities and self-absorbed in his own desires that he treated his responsibilities toward the country rather shabbily.

There were few men more qualified to serve as president than James Buchanan, Jean Baker declares by way of opening. He had served ably in both houses of Congress for decades and been nominated to the Supreme Court more than once. (He kept withdrawing his name for consideration, desirous of the ultimate prize — the presidency.) And yet his administration is universally regarded as the worst in American history, ending with seven states having seceded from the Union and numerous others on the fence about it. Excoriated in his own lifetime, Buchanan protested that he did take action — he ordered one of the two forts that hadn’t surrendered, Fort Sumter, to be resupplied. So there! And he even made a speech that secession is something we mustn’t do, though — dear me, dear me — there’s nothing to be done about it if you were to happen to secede. Nothing in the Constitution, you see? Never mind that Buchanan had gotten aggressive domestically before, in Kansas — though Baker oddly ignores his actions in Panama, another testament to the fact that Jimmy was no shrinking violet.

Baker attributes Buchanan’s inconsistent actions in office to two things: one, he inculcated the formal, procedural nature of the law into his personality. He was not dynamic, able to roll with the changes, and once he’d rendered a judgment or settled on an opinion there was no changing it. He expected that, the law having been issued, it was The Law. If you wanted to change it, there were ways to do that, but they didn’t involve ignoring the law or subverting it. The Lecompton Constitution, for instance, was a travesty, a mean joke — drawn up by an extreme minority of Kansans and sent to Congress to debate. It was, frankly, unconstitutional, containing measures to persecute the free speech of those who opposed slavery — but Buchanan accepted and endorsed it because the Lecompton legislature which had drawn it up was the officially recognized legislature of Kansas, not the freesoiler one in Topeka.

More importantly, however, was Buchanan’s deep investment in Southern social society. Although he’d been raised with a story that Abe Lincoln would appreciate — born to a poor family that turned hard work into success and thriving businesses — Buchanan was no hardscrabble Yankee. He studied law and was deeply appreciative of his southern friends’ more laid-back approach to life. They too, studied law and practiced it and politics, but they were more men of leisure and arts rather than bank books and real estate speculation. Baker writes that Buchanan found their company deeply attractive — far more so than pushy Puritans. He surrounded himself in the White House by men of the South, and his cabinet remained mostly southern even after South Carolina had seceded and men in other states were actively preparing for their self-defense in case Lincoln decided to take the Andrew Jackson approach to secession.

I half-expected when I began this book to end it viewing Buchanan more sympathetically, as happened with my reading of Franklin Pierce. That was not the case, though it’s not necessarily Baker’s fault even though she was clearly not a fan. There was some bleedover from my reading 1858 at the same time and seeing Buchanan’s obsession with Cuba and pushing around Paraguay, and then seeing him here trying to will the slavery issue away — adding fuel to the fire through such aggressive support, feeding more aggression from abolitionists — he strikes me as a man with the wrong priorities. Being a southerner, I suppose I should like him for his partiality towards the South, but his indulging the plantation elite proved not only immoral, but not in the South’s best interests. It probably would have been best for everyone if Buchanan had accepted earlier offers to join the Supreme Court.

Although Baker is definitely not an impartial biographer, I enjoyed learning about Buchanan’s early life, and this combined with the other two works I was reading gave me a better appreciation of how a duck he truly was. Of the three, this is the best for a survey of his life and work, since 1858 and Bosom Friends are more focused in scope. Given that Bosom Friends focuses on Buchanan’s social life, particularly the “Bachelor’s Mess” he kept with William Rufus King and several other legislators, I’m hoping to end this miniseries within my larger “impending crisis” obsession on a slightly more charitable note. ‘Tis the season.

Quotations

As a loyal member of the Democratic party Buchanan represented one of the few remaining national institutions in the United States when he was elected president. By that time, churches had separated into northern and southern factions; newspapers printed only sectional versions of the events of the day and the new Republican party had no following south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Only the Democracy remained the voice of all the people —North and South.

Buchanan had long since chosen sides. Both physically and politically he had only one farsighted eye, and it looked southward.

Republicans and many northern Democrats considered the invasion of Mexico gross interference in the domestic affairs of another nation. Besides it was illegal to use American troops to invade another nation without a declaration of war by Congress. But the president held Mexico an exception to such constitutional strictures. It was a neighbor whose “anarchy and confusion” affected Americans. “As a good neighbor shall we not extend to her a helping hand to save her?”

Measured against other presidents, even those in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Buchanan is one of the most aggressive, hawkish chief executives in American history.

Americans have conveniently misled themselves about the presidency of James Buchanan, preferring to classify him as indecisive and inactive. According to historian Samuel Eliot Morison, “He prayed, and frittered and did nothing.” In fact, Buchanan’s failing during the crisis over the Union was not inactivity, but rather his partiality for the South, a favoritism that bordered on disloyalty in an officer pledged to defend all the United States. He was that most dangerous of chief executives, a stubborn, mistaken ideologue whose principles held no room for compromise. His experience in government had only rendered him too self-confident to consider other views. In his betrayal of the national trust, Buchanan came closer to committing treason than any other president in American history.

Throughout the war Buchanan was a good Unionist. He supported the draft, but not the Emancipation Proclamation, and he never publicly criticized what he considered Lincoln’ violations of the Constitution.