WHAT have you finished reading recently? The Gulf, a big ol’ history of the Gulf of Mexico, which I’ve fallen for completely. I don’t mean beach-combing and eating shrimp & grits, I mean just being smitten by the energy of the ocean and the landscape it creates.

WHAT are you reading now? Eruption, James Patterson based off of….Michael Crichton notes? I am not impressed so far. I am distinctly underwhelmed. I don’t even know if I’m whelmed, frankly. I’m also listening to The Skeptic’s Guide to Alternative Medicine by Dr. Steven Novella, host of The Skeptics Guide to the Universe, publisher of a book by the same name, and owner-author of Science-Based Medicine. It’s on Audible, so it’s…..maybe….an audiobook?

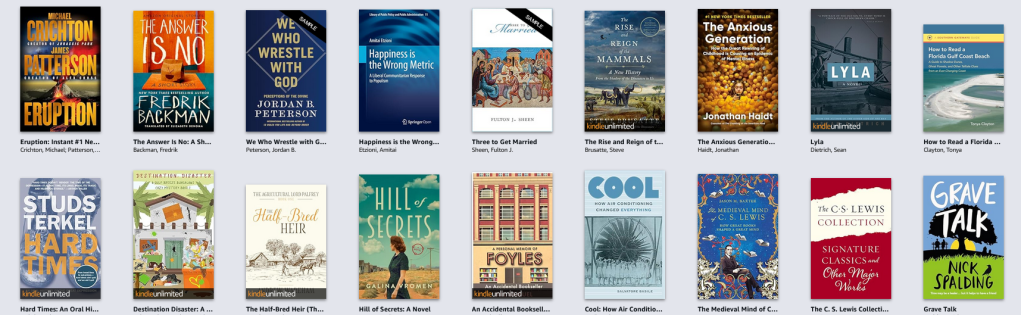

WHAT are you reading next? I should be reading more SF for Sci Fi Month, especially considering I’d intended to read Left Hand of Darkness. Also looking at We Who Wrestle with God, a presumably interesting book by Jordan Peterson who has quite a few fascinating lectures on the Bible on Youtube, which examine its stories and meaning in a psychological/philosophical context. Here’s the chaotic Kindle pile:

Today’s prompt from Long and Short Reviews is: whaddya do on the weekend?

That varies a little depending on the season of year, of course. Default activity for the last year has been to do movie night with friends on Friday night, movie night with friends on Saturday, and church + breakfast with friends Sunday morning. I also work every other Saturday. Now that summer’s misery is over, I’m going to more events like chili cookoffs and the like, and I recently found myself ‘surprised by joy’ in a relationship (with someone who would get that reference), so there’s that.

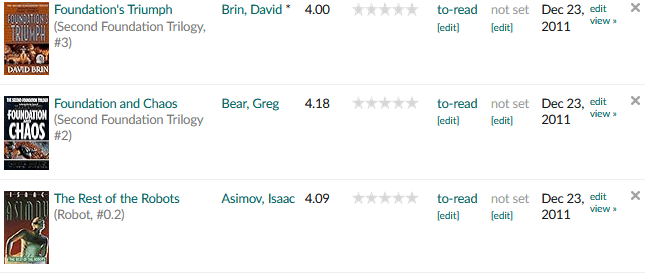

Today’s prompt from Sci Fi Month was supposed to coincide with Top Ten Tuesday, focusing on the oldest SF on our TBR pile. I don’t even know that I have any SF on my goodreads TBR pile, but I’ll look.

(1) Dangerous Visions, ed. Harlan Ellison. With or without goodread’s help, this is a SF title that’s been on my list ever since Isaac Asimov mentioned it (repeatedly) in his ruminations on SF. It’s been out of print and terribly expensive, but in recent years has become much more affordable. This is a collection of SF stories from 1967 from various authors, and became the beginning of a series.

2-4:

Two of these are from a Foundation-based series penned not by Asimov which I’ve not tried, the rest would be an Asimov collection propler. Unfortunately, as with Wendell Berry and PG Wodehouse, at this point I’ve read so many diverse collections I have no idea how much of The Rest of the Robots I’ve read already and which I’ve not. I mean, I have The Complete Robot, which sounds comprehensive, no?

#5 Tarkin. I like Tarkin more than I should. He’s a lovely villain and hilarious in his hypocrisy: he goes from fooling Leia and smirking — “You’re far too trusting!” — to being personally insulted that “She LIED to us!!”

#6: Master Class. As I remember, it’s about technocracy and elitism.

….and that’s it for the Goodreads list. Add to that Star Trek: Firewall, Star Trek: Asylum, and we’re at 8. Add Delta V and some Firefly to give us ten.