Today’s TTT is top ten books on our spring TBRs — but first, the tease!

It was indeed a sweltering day, but before she could turn on the air-con, she needed to expel the stale air of yesterday and let fresh air in. When will I escape from the past, or is that a futile task? (Welcome to the Hyunam-Dong Bookshop)

“When I tell people what I’m telling you, they laugh at me,” Smoke said. “They didn’t used to, but they do now. They act like I’m something out of another century, some kinda throwback. I am, I guess. I’m a ——- arachnidism,” Smoke said.

“You’re a spider?” (Out of Range)

And now, books I plan on reading this spring!

(1) Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty, Charles Leershen. A modern biography of Cobb that addresses the libel written about the Peach by the likes of Al Schmuck.

(2) The Confessions, St. Augustine. Translated by Anthony Esolen. Reading for Lent and Classics Club.

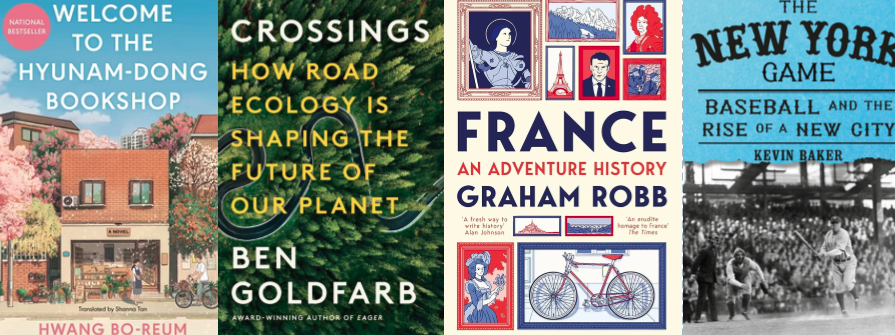

(3) Welcome to the Hyunam-Dong Bookshop,Hwang Bo-reum. Translated by Shanna Tan.

(4) Real England: The Battle against the Bland, Paul Kingsnorth

(5) France: An Adventure History, Graham Robb

(6) Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet, Ben Goldfarb

(7) Mansfield Park. A classics club entry and the last of Austen’s adult novels I’ve not read. Why does it have to be so big?

(8) The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City, Kevin Barnes.

(9) Star Trek. I have two new — well, published last year new — ST books I’ve not picked up yet.

(10) More CJ Box!