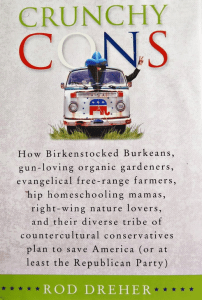

Eleven years ago I stumbled onto a book called Crunchy Cons by Rod Dreher. I’d begun moving towards ‘localism’ in my later progressive period (circa 2009 – 2011), and had found unexpected insight in online magazines with some localist-oriented writing like Front Porch Republic and The American Conservative, the latter of which Dreher wrote for. Though then still a progressive, the part of me that yearned for cooperation rather than partisanship found the magazine incredibly interesting: TAC writers’ New Urbanist and anti-war writing were nothing like I expected of Republicans. Something about Dreher especially intrigued me, and I sent off for this title. Although my review was mixed at the time, it would be the beginning of a long literary relationship with Dreher. He’s since become an absolute favorite — the only author I’ve ever wanted to meet, and in fact have done several times now. Because so much has changed in the last decade — myself, the world, Dreher himself — I wanted to go back and see what would happen.

The premise of Crunchy Cons (2007) is that there is a growing conservative counterculture, one created by the increasing lack of a difference between the uniparty’s wings, and more importantly the fact that political policy is failing, or simply can’t, address people’s needs for meaning and an authentic life. Instead, both parties, and indeed the general zeitgeist of modernity appear to see humans as purely economic creatures, getting and spending: the economy and material concerns are all they promote. While it’s common to associate the counterculture with 1960s-70s young people who scorned materialism and the ‘burbs and yearned to go back to the land, Dreher writes that there’s a kindred conservative counterculture that is rapidly emerging as creature-comfort goals continue to numb our souls and make it hard for us to breathe. (Okay, the Monkees reference was mine, I’ll admit.) He refers to these fellow travelers as “crunchy cons”, and offers that one thing that unites them — regardless of location, religion, etc — is an emphasis on “living sacramentally”. That phrase is one hard to define, but one I understood almost immediately — living with meaning, perhaps, and living and acting with intention.

What we do matters, Dreher writes, as does how we live. Consider our relationship with food. He devotes an entire chapter on our relationship with the food supply, questioning whether those who consider themselves conservative Christians can countenance a food supply based on horrors like confined animal feeding operations, where thousands of creatures live miserable existences, filled with medications to counterbalance the insanely unhealthy setting. Is this ‘dressing and keeping the garden’? — or is it plundering it? Against this, Dreher offers his and his wife’s experiences with their local organic farm’s CSA, and points out that not only is the food healthier from a nutritional point of view, it’s building relationships and contributing to creation rather than abusing it. Farmers like Joel Salatin and Wendell Berry (who has a heavy presence here) restore Earth through their husbandry, rather than consume it the way industrial agribusiness does. While Dreher believes the free market is still the best economic approach on offer, he’s staunchly against deifying it, or worse still, deifying Efficiency. CAFOs have made chicken cheap, but the price is exacted elsewhere — in the quality of the food, in the destruction of our right relationships with animals and the land, in the predatory ways big-ag treat their suppliers, who are sometimes little better than tenant farmers . Chasing cheapness in other areas has its prices, as factories shutter and the towns and families that depended on them fall apart. We ought to live in such a way that grace is present, that holiness comes down to Earth. On the subject of living gracefully, there’s a strong aesthetic sensibility in this, one that appears not only in the food chapter but throughout: Dreher argues for slowing down and focusing on the good, the true, and the beautiful, rather than thoughtlessly participating in the rat race. He and his wife made the decision to simplify their lives so that they could raise their children without daycare, and later doubled-down by homeschooling them to maintain participation in their lives. For the Drehers, family mattered far more than chasing the Joneses.

This was a fascinating book to return to, originally reading it as I did during a transitional period in my life — and not necessarily a transition I was at ease with. I had to laugh at the amount of overlap between books Rod and I had both read before I picked this up, and books he mentioned that would later have a big impact on me. Wendell Berry, as mentioned, is a heavy presence here, but I hadn’t yet discovered him — and while surely his insight would have of interest to me at the time, I didn’t read Berry until later that year, prompted not by this but by a Art of Manliness booklist recommending Jayber Crow. While reading this, I tried to remember my cast of mind in 2012 – 2013: it was a time of both confidence and confusion, as physically I’d gotten on a health kick and was really enjoying life, but mentally my college worldview had fallen apart and I was reading far and wide looking for answers. Currents of thinking and reading were not taking me to places that my “self” at the time necessarily wanted to go, though: this was back when reading Hayek and Kirk felt positively transgressive. When I read Crunchy Cons the first time, a lot resonated with me — more, I think now, than I was comfortable with at the time, hence the mixed review. In my head, I was still the confident college progressive: realizing my thinking was increasingly at odds with that identity was just as uncomfortable as my secular-humanist college self finding the writings of mystics and monks inexplicably fascinating.

It’s amusing to read that review in retrospect because of the way my thinking and my values have changed over the years: 2012 me was not too far removed from my Pentecostal past and my emotionally charged exit from it, and so was more hostile toward Dreher’s homeschooling his kids for religious-values reasons, among others, then ignoring the fact that his wife’s cohort of homeschooling moms were largely liberal women who wanted to be more involved in their children’s education and life and believed they could do it better than a teacher having to deal with a hundred kids a day. These days I’m far more critical of the public education system — having witnessed it via the library for 13.5 years now. What’s more, I regard a system in which parents are separated from their children for most of the day as profoundly abnormal and unhealthy, just as it is unhealthy for children whose very being wants to bound into the world instead be confined into boxes all day, compelled to stare at screens and work on developing their future emotional-mental disorders. While it’s easy for me to say that this owes in part to my ingesting a Chestertonian or say, Catholic view of the family over the years, I think it has deeper roots than that. I resonated with the Catholic social doctrine when I began studying it around this time (2014, I think) for the same reason I resonated with the Buddhist eight-fold path’s emphasis on “right livelihood”: there’s something in me that recognized the need for an integrated or holistic approach to life that serves the needs of the human person — not only our material needs, but our need to live the good, to have lives shaped by virtue and wisdom in which the various roles we play are not separate, but like the petals of a flower creating a beautiful whole. This emphasis on human flourishing has been one consistency in my thinking from say, 2006 forward.

I rather enjoyed going back to this, and the challenge it and my first review posed to me to reflect on my worldview as it changed. When I began reading it then, Rod and I already had points of agreement: a strong criticism of consumerism, a worldview that rejected materialism, and an interest in slower, simpler living. Areas where we diverged, like Rod’s more observant religion, I’ve actually grown closer to: back then I was a church-goer, yes, but liturgy hadn’t seeped into my soul yet, and I hadn’t yet gotten serious about Christian formation and praxis the way I would in the years to follow. Reading this made me like Rod all the more, simply because of the amount of bookish overlap we have: I’d read books he references, and in the years to come I’d read others he referenced, not because he referenced them but because that was where my currents of thought were taking me. Wendell Berry, for instance, would become a favorite in both nonfiction and fiction. There was additional interest in seeing how Rod’s thinking would develop over the years, with some chains of thought that would lead to The Benedict Option and Living in Wonder. His interview with Catholic and Orthodox crunchies also hinted at storms to come in Rod’s life — his already present anger and grief over the Catholic church’s behavior during the sex abuse scandal, and his attraction to Orthodoxy. While I can’t say “in short” given the length of this review, I can only reiterate how much I enjoyed going back to this, both for my fondness for the author and for the amount of thought it provoked as I read it.

So Many Quotes

Maybe instead we should create a new politics by asking: What’s good? What’s true? What’s beautiful? What’s authentically human?

Too many people who call themselves conservative share the same fundamental conviction of many liberals, namely, that individual fulfillment is the point of life. Conservative, perhaps, in their sexual views, they are, however, libertarian in their economic principles, and believe that the free market should be the guiding light of our lives together. Thus they believe that a merchant or a manufacturer owes no loyalty to his community, nor the community to that merchant or manufacturer. They feel no particular responsibility to be good stewards of communal life or the natural world; if something of real value has been lost because of economic decisions, hey, that’s the free market. Cultivating an appreciation for art, architecture, and the world of beauty used to be considered by a previous generation of conservatives the mark of a civilized person; today, it is often disdained by many mainstream conservatives as an elitist pursuit. A college education is something you get solely as a ticket to a moneymaking career.

There is an older, less-ideological tradition, a sensibility that comes out in people I call crunchy conservatives. We are conservatives by conviction and temperament, and usually vote Republican (though to call us “liberal Republicans” is to fundamentally misunderstand us), but we’re “crunchy”—as in the slang for “earthy”—because we stand alongside a number of lefties who don’t buy in to the consumerist and individualist mainstream of American life.

Mainstream liberalism and conservatism, as the agrarian essayist Wendell Berry said, are “perfectly useless” to combat the forces in contemporary American society that are pulling families and communities apart. Berry says most liberals won’t take a stand against anything that limits sexual autonomy, and most conservatives won’t oppose anything that limits economic freedom.

The liberty we enjoy in America today is certainly worth prizing and defending, but it is insufficient to produce virtue, stability, or happiness. The free market in ideas, commerce, sexuality, and so forth offers various possibilities of how to live, but it tells us nothing of how we should behave to live as well as we ought. Both mainstream liberalism and conservatism are essentially materialist ideologies, and we should not be surprised that both shape a society dedicated to the multiplication of wants and the intensification of desire, not the improvement of character.

The answer is not to be found in a set of policy prescriptions, but in a considered critique of the assumptions on which mainstream American life is built, and a secession of sorts from the mainstream —all to conserve those things that give our lives real weight and meaning. Every one of us can refuse, at some level, to participate in the system that makes us materially rich but impoverishes us spiritually, morally, and aesthetically. We cannot change society, at least not overnight, but we can change ourselves and our families.

We should ask ourselves what kind of society we want to live in, and want our descendants to live in, and ask whether the way we’re living today is likely to get us there. Ideas have consequences, after all, and too many conservatives have unthinkingly accepted the mainstream Republican view that there is nothing wrong with the country that the free market cannot x, at least over time. Unmoored from our philosophical grounding, we allow ourselves to be carried along on the swift currents of consumer culture, and end up in a place where “conservatism,” practically speaking, ends up as general approval of whatever commercial interests want to do.

We have become a society that gives the place of prime honor to material progress, placing the demands of the economy above the considerations of family, of community, of country, and even of religion. Consumerism has become our religion, and it is difficult to identify anything within the contemporary Republican Party that stands against the dogma of the Market Supreme.

Americans naively accept new technologies, thinking only of what these technologies can do, but never, said Postman,what they can undo.

“The number one advice I give to my students is to be a culture creator, not a culture consumer,” Schuchardt continued. “You have to have time to create, and to create, you have to get rid of those things that steal your time. TV is the great time-stealer in American life.”

A society built on consumerism must break down eventually for the same reason socialism did: because even though it is infinitely better than socialism at meeting our physical needs and gratifying our physical desires, consumerism also treats human beings as merely materialists, as ciphers on a spreadsheet. It cannot, over time, serve the deepest needs of the human person for stability, spirituality, and authentic community. We should not be surprised that it has led to social disintegration. What kind of economy should we have, then? I don’t know; I’m a writer, not an economist. I do know this: we can’t build anything good unless we live by the belief that man does not exist to serve the economy, but the economy exists to serve man.

The point is, we learned in this way that food, properly understood, is sacramental; it carries within it the care of the farmers who raised it and the merchant who sold it, the love and devotion of the hands that prepared it, and the happiness of the friends and family who share it.

I started looking into how the government regulates the meat industry. It was shocking to see how agribusiness has gamed the system to keep small meat producers marginalized. Our regulatory system is designed to favor industrialized meat production, with its factory farms, its cattle jacked up with antibiotics and growth hormones, and its chickens raised in cages filled with their own feces. As a conservative, I am angry about this, not only on behalf of the small businesspeople slapped around by the deep-pocketed agribusiness behemoths, but because of how industrialized agriculture has made a traditional agrarian way of life difficult if not impossible.

When I asked Robert what he has in common with liberal counterculturalists, he said that there’s a lot of antiestablishment contrariness in all of us—echoing the quip of Juli Loesch Wiley, a Catholic pro-life pacifist friend who says she went all the way from the left wing to the right wing without ever once trusting the government. (Hah!)

But something struck me, a quote by Saint Francis de Sales, who said that we should treat everything we have as a gift from God, and that we are a gardener caring for the king’s garden. That struck me so much, because what I’m talking about is the body as the temple of the Holy Spirit. I don’t see how God could be pleased by the way so many of us eat. And that’s what motivates me. It’s stewardship of the body and of the earth. I just don’t understand why people have a problem with that.

How long do you think we can keep living as we do, destroying country life, rural traditions, and the countryside to produce mountains of processed food that makes us less healthy, and letting lay fallow the sacred trust we’ve been given by our forebears? Care for this trust obliges all of us, but conservatives, because we profess a particular commitment to upholding tradition, are especially responsible for stewardship of the land and its cultural legacy. If we live as if we have no duty to the land and the agrarian traditions of the people who live there, then we ought to be ashamed to call ourselves conservatives. We are no more than market-mad consumers who vote Republican, and whose commitment to conservative ideals ends the moment it costs us something.

If you’re like me, you’ll find as you grow older a strange new respect for the middle-class clichés you spent your smart-ass youth making fun of. Knife. Fork. Crow.

Thought experiment: You are standing at mass in the great Gothic cathedral at Chartres, beneath the vast symphonic complexity of the building’s soaring arches; now you are standing at the same ceremony inside an equally vast modern American suburban megachurch, which looks like an expensively built gymnasium or theater. Theologically, the ceremony has precisely the same meaning. But in which place do you feel closer to God, more aware of the holiness of existence? From which of these churches are you likely to emerge with a glow of exaltation? If a terrorist with a truck bomb forced you to choose which of these structures you’d rather see destroyed, would it make a difference to you? Why?

Notice: “outside of the norm that you see on TV.” The mark of the twenty-first-century nonconformist—the ability to imagine a life outside of the boundaries set for us by media culture.

“The common agonies we call ‘socialization’—playground cruelties, intimidating classroom snickers at mistakes, disabilities, or differences—more often serve to harden than to heighten the child’s sensitivity to other people’s pain. Homeschooled children for the most part don’t have to deal with that, and are more likely to retain their natural compassion.

Technology and wealth have given mankind dominion over nature unparalleled in human history. Everything in the tradition of conservatism— especially in traditional religious thought—warns against misusing that authority. Yet the conservative movement has become so infatuated with the free market and human potential that we lose sight of what Matthew described as our conservative belief “in man as a fundamentally moral and not merely economic actor, a creature accountable to reason and conscience and not driven by whim or appetite.” If we lose our ability to see nature with moral vision, we become less human, and more like beasts.

“Conservatives I respect a great deal are always telling us that man is not just an economic being, but a moral actor,” he said. “Well, there are moral costs to efficiency.”

“In America especially, we live beyond our means by consuming the portion of posterity, insatiably devouring minerals and forests and the very soil, lowering the water table, to gratify the appetites of the present tenants of the country,” [Russell] Kirk wrote.

Almost all on the religious right are Christians—and in this broad sense, I am on the religious right—but it’s odd how we limit our political concern to sexual issues. Jesus had as much or more to say about greed as he did about lust. But you will not find most American religious conservatives worrying overmuch about greed.

To see the world sacramentally is to see material things—objects and human actions—as vessels containing or transmitting ideals. To live in a sacramental world is to live in a world pregnant with meaning, a world in which nothing can be taken for granted, and in which no one or no thing is without intrinsic worth. If we live sacramentally, then everything we do and everything we are reflects the things we value.

In short, if one’s religion is to mean anything, if it is to last, it has to stand outside of time and place. Its truths have to be transcendent. And though we moderns have to nd a way to make the tradition livable in our own situations, we must never forget that we don’t judge the religion; the religion judges us. To be blunt, a god that is no bigger than our own desires is not God at all, but a divinized rationalization for self-worship.

“I don’t understand why the social-justice people don’t drop their attachment to socialism and embrace the ideal of widely distributed property,” he said. “I don’t understand why patriotic conservatives don’t seem to care that soulless corporations are destroying the old weird America—a phrase coined, I think, by left-wing rock critic Greil Marcus. This is the rich, vital, genuinely diverse, eccentric America that conservatives love, or claim to love.”A religion in which you can set your own terms amounts to self worship. It has no power to restrain, and little power to inspire or console in times of great suffering. No matter what religion you follow, unless you die to yourself—meaning submit to an authority greater than yourself—it will come to nothing.

American politics has come to resemble the First World War, when powerful armies clashed endlessly and fruitlessly, with neither side gaining much ground, both having forgotten what they were fighting for, remembering only who they were fighting against.

I can see how you found this attractive. Some of those quotes make a LOT of sense.

He was and remains a thought-provoking author. He’s CONSTANTLY reading.

Pingback: The Last 10 Books Tag | Reading Freely

Pingback: Against the Machine | Reading Freely