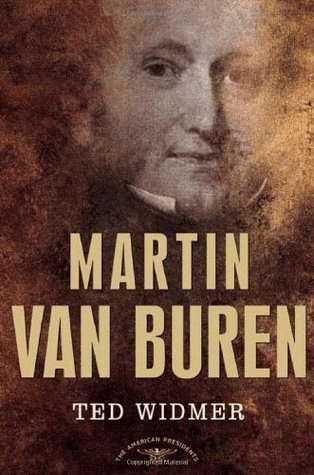

Who is Martin Van Buren? When I cast the name into the pool of my imagination, I can see his face reflected there, framed by wild sideburns and seeded by a guide to the US Presidents I read cover to cover obsessively in middle school. (It covered everyone from George W to George W.) The trivia factoid assigned to him in the book was that he was the first US President to not be a subject of Parliament when he was born, though frankly knowing he didn’t speak English when he was young would’ve been more interesting. I picked this book up as part of an old-but-rarely-pursued course of presidential biographies that I’ve gotten more interested in continuing as America’s 250th looms. Ted Widmer’s Martin Van Buren is a short and often punchy biography of this singular figure in American life, a man frequently forgot despite having a large ‘quiet’ role in how American politics developed in the early 19th century.

Van Buren, it seems, was instrumental to the creation of the Democratic party, which he forged in an effort to reconcile the interests of New York and Virginia. He had a knack for party organization, in fact, building a machine in New York before he ascended to the national stage. He came of age when the balance of economic and political power was slowly starting to shift from the South to the North, and would ride that transition — ultimately helping create the Free Soil party, precursor to the Republican party that later Democrats raised quite a fuss about in 1860. The book largely focuses on Van Buren’s political career, so that it’s hard to get a sense of the person underneath the president. At first I thought this was a fixation of the author, but after doing more background reading it appears to be a consequence of the man himself. He was widowed early and focused obsessively on his work: his ‘leisure’ activities of reading, socializing, and travel were all fastened to politics as surely as a bridle to a horse. He appears to have met luminaries of different ages — visiting with John Adams and Thomas Jefferson in their declining years, serving under Jackson’s tutelage, and still later enjoying an evening with a young lawyer named Abraham Lincoln, quite by accident. (During a grand tour of the country, Van Buren was forced to hole up for the evening in a little inn in Rochester: the proprietor was so eager to amuse his unexpected guest that he sent for a storyteller and raconteur he knew had an interest in politics.)

This was an interesting little read. The writing is very accessible and sometimes drift toward being overly casual to me, but it’s often funny despite the fact that the main attraction is a man not known for great policy decisions but instead the quiet under-the-table work that makes modern politics function. While Van Buren still feels like a bit of a cipher, considering that he rarely wrote about himself in his own journals, it’s possible that no one but his late wife knew him beyond the civil but savvy political creature he was.

And on a completely unrelated note, nonfiction has FINALLY CAUGHT UP from the three months of CJ Box. Also, my next obscure president will probably be Franklin Pierce.

Quotations

In the long annals of the presidency, it would be difficult to find a presidential spouse we know less about than Hannah Van Buren. There are no likenesses of her, and she died long before Van Buren was elected. She is not mentioned in the enormous manuscript of his autobiography. Yet there is not the slightest whiff of scandal about their love, and it is telling that he never remarried after her death in 1819.

We have lost the sense of what the law once stood for to ambitious young men. As the nineteenth century dawned, it still commanded an awe that transcended the political realm. Lawyers were the priests of a secular order. Their learning was majestic: their Latinate vocabularies, their parchments, their stately mien, their effortless command of the Common Law, the repository of Anglo-Saxon cultural habits dating back half a millennium. The United States may have been writing a new chapter in human history, but its lawyers, the people who really ran things, were part of an ancient guild connecting them to the Middle Ages. Tocqueville wrote, with understatement, “The government of democracy is favorable to the political power of lawyers.”

Just as Lincoln would do in Illinois, he traveled the circuit, talking about people and politics everywhere he went. One source claims that he was developing a useful skill for a politician—the ability to walk into a tavern and hold an enormous amount of alcohol without any sign of impairment.

In 1842, Jabez Hammond published The History of Political Parties in the State of New York, in three octavo volumes. If you can even find it in a library, there is a good chance that you will be the first person to have taken it out in a century and a half. Yet beneath its ancient leather binding, the brittle pages teem with life.

But as usual, many of Van Buren’s best moves took place far from the public eye. Like a nineteenth-century Vito Corleone, he was always thinking ahead of his enemies, forging a new network of families and alliances that would forever redraw the map of power in the United States. Everything he did contributed to the goal of unfurling a new national party, nominally Jeffersonian but now hitched to the rising star of Andrew

Jackson.

None of this activity was lost on President [John Quincy] Adams, who could not have looked upon Van Buren’s activity with more disfavor if he was an emissary from the Vatican seeking to convert Yankee maids to Papism and then sell them into white slavery. In one of his most vituperative journal entries, he managed to disembowel Van Buren for reasons ranging from his parentage to his politics to Aaron Burr’s treason (the Adamses were nothing if not efficient—why write only one insult when three would get you so muchmore for your ink expenditure?).

Since Dolley Madison’s benign rule over Washington in the teens, a formidable force had been gathering strength in the capital—the influence of political wives. Nearly as soon as the British retreated, they advanced, and in the 1820s, as Washington became less an architectural sketch and more a genuine community, it was inevitable that these powerful spouses would feel their growing power over the destinies of the young republic. And they would advance their power through what passed for weapons of mass destruction at the time: gossip, innuendo, and outright slander.

Even later that spring, when he might have recanted, he refused, saying he would not trim “his sails to catch the passing breeze.” This was Van Buren at his best.

It would take a long time before the wounds of the 1844 convention were healed. Thomas Hart Benton, Van Buren’s friend from Missouri, saw a dark design behind the scenes in Baltimore: “Disunion is at the bottom of this long-concealed Texas machination. Intrigue and speculation cooperate; but disunion is at the bottom; and I denounce it to the American people. Under the pretext of getting Texas into the Union, the scheme is to get the South out of it.”

Charles Sumner, who hardly would have defended the old Van Buren, admired “the Van Buren of to-day,—the veteran statesman, sagacious, determined, experienced, who at an age when most men are rejoicing to put off their armor girds himself anew, and enters the lists as the champion of freedom.

That was a more than respectable performance, especially given that the Free Soil party could not get on the ballot in the South, with the exception of Virginia, where Van Buren won a grand total of nine votes. When some of his supporters claimed fraud, a Virginian answered memorably: “Yes Fraud! And we’re still looking for the son-of-a-bitch who

voted nine times!”

Throughout the decade before the Civil War, Van Buren enjoyed seniority among the ex-presidents, ultimately resembling one of the elderly patriarchs invented by Faulkner, who outlives first his own cohort, then his children’s, until no one is quite sure who he was in the first place.

Van Buren had only so much revolution in him. In 1858 he told a visitor, “I have nothing to modify or change. The end of slavery will come—amid terrible convulsion, I fear, but it will come.”

He lingered into the war’s second year, and then expired at 2 a.m. on July 24, 1862, a day and a half after Lincoln read the first draft of his Emancipation Proclamation to a startled cabinet. Van Buren could hardly have chosen his entrance and exit more dramatically.

But to this day, there have been sufficiently few biographies of Martin Van Buren that a reader with time on his hands (and what other kind of Van Buren acolyte is there?) can reasonably expect to read every work on Van Buren ever written—something that would be impossible to say about the other giants of the early republic

.