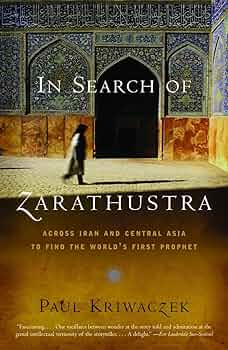

Today is the Feast of the Epiphany, in which Christians celebrate the arrival of the Magi to Bethlehem. It is fitting, then, on this day about wise men of the east following stars, to take a look at at a Persian whose own view of the heavens has influenced at least three major world religions. Zarathustra or (Hellenized, Zoroaster) is a name I’ve been bumping into for twenty years, in my efforts to understand the evolution of Judaism and Christianity; when I saw that the author of a history about Babylon had done on the famed ‘prophet’, I was eager to read it. I was expecting a history of what Zoroastrianism is and how it influenced other religions — particularly Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, with their shared vision of a Messiah at the end of history. It is, sort of, but not as organized or formal as all that: Kriwaczek instead mixes history, tourism, religious exploration, and literary analysis to follow not only the way Zoroastrian beliefs and praxis still exist under a Muslim or Eastern Orthodox skin in parts of eastern Europe and Central Asia, but how various religions and philosophies that drew from Zoroastrianism (Gnosticism and Manicheanism, especially) shaped history across Eurasia. As a study into the complexity of religions and cultures, it’s absolutely fascinating, seeing how much intermixing there is between cultures — and remixing, in the case of the Roman adoption of the Iranian Mithras cult. Kriwaczek suggests that Mithras was a figure in primitive Iranian mythology who, at the development of Zoroastrianism, was elevated to be a figurehead or liaison between the ‘good’ deity of Zoroastrianism, Ahura Mazda, and the people. Unfortunately, Kriwaczek does not assay Zoroastrianism itself: the lay reader will get the idea that it was archly dualistic, with a Good Deity and a Bad Deity fighting, and that light (and especially fire) and spirit were associated with the Good Deity while the Bad Deity was associated with darkness and things of the world. There is, however, no real detail on practices, theology, etc. What I was most curious about was Zoroastrianism’s potential effect on Judaism and Christianity, turning the quality-control inspector of Judaism[*] into the Archfiend, the antagonist of God who hates him and all his works — but that isn’t address beyond exploring various Christian heresies that took their inspiration from Zoroaster’s arch-dualism. Happily, Kriawczek does spend time dwelling on Apocalypticism, which is still part of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam today — though it is central to Christianity, of course, given that Christians believe Jesus to be the Messiah who heralds the End of Days and triumphs in the last epic battle between Good and Evil.

Although this is a bit scattershot, rather like his Babylon, I enjoyed it enormously, in part because the huge mosaic of humanity that encompasses, and the thread uniting such a variety of beliefs and practices.

Highlights:

For the Iranian world has had to suffer foreign conquest on all too many

occasions: Alexander, Genghis, the armies of Islam, Tamerlaine, Babur.

One after another they came, they saw, they conquered and they destroyed.

Everywhere throughout the country, the ruins left by successive invasions

still dot hillsides and valley floors: castles whose entire garrisons were put

to the sword; townships abandoned and never resettled; walled villages of

sun-dried brick, forever bereft of population and slowly crumbling back to

the dust from which they were built. And each time Iranian civilisation and

culture discovered a way of surviving, of rising again from the flames like a

phoenix, of clothing its old ways in new clothes.

“My Iranian companion tried to bend the truth a little: ‘I am from the

Ministry of Antiquities in Tehran,’ he said grandly, waving a grubby scrap of paper in front of the man’s nose.

‘Oh no you’re not,’ said the man with total conviction.

My companion was rather taken aback. ‘Why do you say that?’

‘No government official from Tehran ever got up so early in the

morning.'”

[*] A Jewish website that I read 15+ years ago but cannot find now used the character of “Mr. Slugworth” from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory as an illustration of Satan’s role in Judaism. In that movie, a man who identifies as Willy Wonka’s rival but who is in fact an employee of Wonka tests the children visiting the Chocolate Factory by bribing them, asking them to filch an Everlasting Gobstopper so his company can reproduce it. All but Charlie fail.

Cool. As I have this – its been sitting on my shelf for AGES – its good to know that its so interesting. Maybe it’ll get read *this* year…? [grin]

Well, like anything it helps to have a pre-existing attachment to the subjects — in this case, both Zoroastrianism and central Asia..

Pingback: January 2024 in Review | Reading Freely