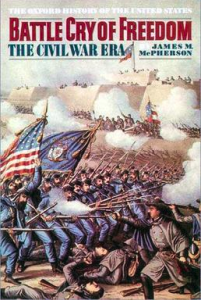

Battle Cry of Freedom is widely regarded as the finest single-volume history of the Civil War — and after finally reading it, I understand why. McPherson compresses an era of extraordinary complexity into a narrative that feels both sweeping and intimate. Although McPherson begins in the 1850s to lay the groundwork for secession, the book never bogs down; once the shooting starts, he manages to keep the guns of military, political, and social history firing together in concert. The result is a portrait of the Civil War era that feels alive: battles and generals appear alongside labor unrest, civilian hardships, and the illicit trade that persisted despite wartime edicts. Rather than distracting from the conflict, these episodes show how deeply the war reached into ordinary life. It draws from a deep well of primary and secondary resources, so many that I had to stop writing down books I wanted to look in for fear of making my TBR even more of a goliath than it is. Thorough, diverse, fair, and eminently readable, Battle Cry fully deserves its reputation as a masterpiece.

Battle Cry of Freedom begins in the decades before the Civil War, as sectional divisions grew. This was partially aided by immigration patterns: Germans and Irishmen who arrived to begin working their way into an American life had no experience with slavery, and were immune to the “That’s just the way it is” mentality that functionally maintained slavery for decades after the revolutionary generation declared that all men were created equal. A second Great Awakening also increased religious fervor, and in a direction that viewed slavery as inherently sinful, an offense against the notion that all men were created in the image of God, and deserved accordant dignity. Of course, there had been sectional disputes from the beginning of the Union, because different areas of the country had different economies and interests. Tariffs that protected northern manufacturers did so by raising the overall price of manufactured goods in the largely rural South, where the ease of making money from massive plantations made risky factory ventures far less common. As Americans and immigrants continued to pour west, different economic interests led to armed and bloody conflicts, as in Kansas.

Battle Cry of Freedom’s military portions include both the Eastern and Western theaters, though casual readers should know by ‘western’ we are discussing Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky. The Texan invasion of New Mexico is not included. This is not purely a military history, though: McPherson focuses on it when momentum is important, but otherwise takes breaks to look at home front issues, changing politics, etc. The book makes it clear from the beginning that the war’s origins are complex: it was caused by slavery, but not necessarily about slavery, save for a vanishing minority of Union soldiers and Confederate planters. The majority of Union soldiers fought to preserve the Union and in outrage that a fort flying the Stars and Stripes had been fired upon; Southerners had viewed the North with increasing animosity for decades and fought to create a new, southern Confederacy that would remain truer to the Constitution as they interpreted it. McPherson’s early chapters do an excellent job of bringing the secession crisis to a boil: the more popular and militant abolitionism grew in the North, the more entrenched the southern elite and southern culture in general became about the slavery issue. A “necessary evil” in 1800 had become a positive good by 1860. Lincoln was extremely cautious about any anti-slavery rhetoric or measure at the beginning of the war, in large part because the loyalties of several states (Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland) were not guaranteed. This meant offering assurances in the early part of 1861 that no anti-slavery measures were contemplated, and even during the first two years of the war Lincoln countermanded the actions of Union officers who attempted to materially weaken the local opposition by declaring their slaves free. This would, of course, become a Union strategy as the war developed: slaves were viewed as material assets of the Confederacy that needed to be removed from the equation. Not only did freeing them diminish the Southern labor pool, but these new wards of the Union could free up soldiers from fatigue duty. The Union’s legal definition of slaves they ‘freed’ at this point tried to side-step the question of emancipation by declaring freed slaves to be “contraband”: seized property. Eventually, Lincoln decided to adopt emancipation as a total-war measure to help speed up the defeat of the rebellion, and it had the double boon of ensuring that Britain and France did not recognize the Confederacy more overtly than they already had, tacitly. Lincoln’s use of the ‘lever of emancipation’ continued to be a problem for him, especially in 1864 when it was revealed he’d rejected several diplomatic forays by the South preemptively because they would not countenance emancipation. (Jefferson Davis was similarly obdurate, but for a different reason: he declared that the South would rule itself, even if slavery vanished and every Southern plantation and city were set ablaze.)

Although I’m fairly familiar with the course of the war from obsessive reading of histories in high school, a book this big could not fail to turn up areas I’d never heard of. The most fascinating unheard of story was the presence of a few political figures in the Midwest who greeted the increasing abolitionist nature of the war with hostility: they proposed to create a new confederacy with other northern states outside of New England where abolitionism was most strident. In addition to racial animosity, they also declared that they were not sending their boys and men to die to free other men who would then drift northward and compete with them for jobs! I also appreciated McPherson’s separate chapters on the coastal and river wars: I didn’t appreciate how many ports were seized by the US Navy from the opening weeks of the war. McPherson also covers bread and draft riots throughout the war: the South’s struggle to feed itself grew worse with Sherman and Wilson’s raids, and many men began deserting to return to their homes to help their wives and children. McPherson does not shy away from the depredations of war, including Sherman’s spiteful attack on South Carolina which had marginal military significance but served to brutally punish the people for secession.

This is, in summary, quite a history. It manages to be comprehensive without becoming overwhelming, and remains surprisingly nonpartisan – recording in the same voice Confederate soldiers focusing their ire on black troops at the Battle of the Crater as the appalling behavior of Union troops marauding through Fredericksburg in 1862, destroying evacuated homes for no reason other than malice. Although I’ve shied away from it for years because of its size, I found the writing so compelling that once I began I could scarcely stop. It is, simply, magisterial.

Selected quotations will be posted separately.

This has been on my MUST READ list for ages!

It lived up to its reputation for me! I think reading For Cause and Comrade and getting an idea of McPherson’s writing style helped finally coax me into trying it.

Very compelling! It’s amazing how an equitable and truthful examination of a tempestuous time in history can cause the rest of us to come to a judicial understanding of all sides. That is a successful feat for an author.

Maybe I will reconsider visiting this when I come to the Civil War Era of my self-education project. : )

He’s an author I plan to read more of, that’s for sure.