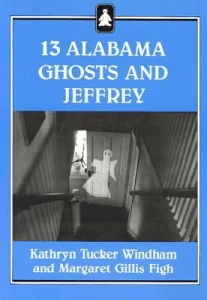

When I was a wee bairn, in the olden days when the Earth was new and dinosaurs roamed the land, I cut my teeth on reading Kathryn Tucker Windham’s collections of ghost stories. KTW, or “Kathryn” as Selmians still call her, was a journalist who loved story telling and oral history: she collected stories and shared them, and I have fond memories of attending festivals at Dallas County’s ghost town, Old Cahawba, and listening to her speak. Her most known books were the 13 ____________ Ghost and Jeffrey” series: I read every single one my library had multiple times. I thought it might be fun to revisit it. This won’t be a formal review, as such, but more of an exercise in reflection.

I should begin by explaining who “Jeffrey” is: Jeffrey was KTW’s mascot, of a sort, a ghost she insisted lived in her home in Selma. This book opens with her experiences with Jeffrey, and I suspect (but cannot remember enough to be certain) that the other books also include a Jeffrey story before she shares ghost stories of Georgia, Mississippi, and so on. She was good enough at promoting him that there’s still a little ‘marker’ of him on our main downdown street:

What follows after the Jeffrey story are thirteen different ghost stories taken from across Alabama, two from my home account of Alabama. They’re all 19th century stories, which is not something I paid attention to as a kid but seemed very salient reading as an adult. One of my coworkers once asked me why I thought ghost stories always seemed to gravitate toward the mid-19th century, and I speculated that it had something to do with the rise of Spiritualism, and that naturally people would have looked to the generation before theirs that was now “lost”. That’s just speculation, of course, and if I wanted to really get out into the weeds I might add that it had something to do with the horrors of the Civil War — the South was littered in death and ruin, and telling stories about spectres from the past kept their memory alive, somehow, or at least provided some way to muse or grapple with the past. Indeed, the War is very much part of most of these stories: a young soldier and his intended taking a walk and being harrassed by spectral balls, a young woman throwing herself to her death after seeing a rider coming with news that her own beau had fallen in battle, and so on. The Selma story included is here one connected to the War, concerning a Mr. John Parkman who made some bad investment choices with Federal money and found himself imprisoned when the market soured. He then escaped, and was somehow killed: I say ‘somehow’ because the manner of his death varies on the manner of his escape:there are various stories as to how he was killed. At any rate, some three years later the servants at his house in Selma (now known as Sturdivant Hall, an exquisite example of antebellum architecture that is now an art museum) began reporting that ol’ Mr. John was….back. I do not know why it took him three years to mosey ten miles from Cahawba to Selma, nor why he seems to refer the rear corner of the estate where a fig orchard used to be, but that is how the story goes.

While most of the stories involve visual ghostly presences, there are other stories where the spirits make themselves known by sound: one young woman evidently enjoys tip-toeing down the hall and then playing popular music of the 1860s, though she’s shy and stops if someone tries to sneak into the room. As a kid, the creepiest of these was “The Hole That Never Stays Filled”, the site of a hanging where the resentful ghost continues to maintain the pit that did him in. I was raised in a church where you weren’t supposed to believe in ghosts, so I used to dismiss most of these stories as just people’s imagination. A hole that wouldn’t stay filled, though? Kid-me was not creative enough to think that perhaps locals kept an eye on the place and maintained the hole just to attract tourists. At any rate, the Chattahoochee River destroyed the hole, and that vacuous object we call ‘progress’ has also destroyed the site of Montgomery’s “Red Lady” at Huntington College. Presumably not longer being able to annoy popular society ladies who snubbed her in real life, she now wanders the nearby streets. I can recommend that she haunt the Capri theater nearby: it’s not too far a float, and it’s sufficiently old that new stories can pop out to explain her way.

I am not one to believe in ghosts, but the older I get the more I appreciate folk-memory and folk stories and the cultural continuity they are part of. That is a hope that seems more and more forlorn in these days of liquid modernity, though. Even so, I may read a couple more of these volumes before All Hallows’ Eve, just to re familiarize myself with some of “Kathryn’s” work. Part of my inspiration for reading this was attending the 42nd annual Tale-Telling Festival in downtown Selma last week, a festival Kathryn started. Originally, professional storytellers would share their favorites with the crowd, and then at the “Swapping Grounds”, Selmians who had a gift for telling a yarn would have their own time at bat. These days it’s more about the professional, but folk elements are still included through music — and this last year, a local who likes to sit in the downtown diner and talk loudly to anyone in earshot was invited to speak a little bit.