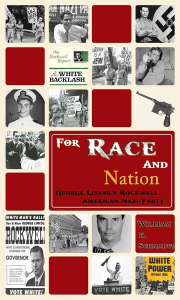

How does a man who fought Hitler come to deify him? George Lincoln Rockwell began life as the child of a popular entertainer, and by adulthood was well-poised for a successful life. He’d gone to a good university, though his education was interrupted by World War 2, and was a gifted illustrator. Instead, political passion for fighting the spread of Communism in the United States made of this Smeagol a Gollum, muttering nastily about Jewish conspiracies. His increasingly entrenched antisemitism cost him his Navy commission, his family, and would later lead to his death at the hands of an embittered follower. How can a soul go so wrong?

There was nothing in Rockwell’s early life to indicate the disturbing course his life would take; his father was well known as a comedian, and socialized with other performers like Groucho Marx. Rockwell’s first blush with racial radicalism and antisemitism came after he finished serving in the Korean War. He had become virulently anti-Communist, possibly as a result of fighting Korean and Chinese communists,, and in meeting with other anti-communists, he encountered literature which attributed communism to Jewish conspiracy. Intrigued, he flirted with taboo and decided to read Mein Kampf, and was so galvanized by it that he fell fully into neo-Nazism, founding the American Nazi Party and buying a home to serve as its headquarters and “hate monastery” , even decorating it with a giant swastika on the roof. Rockwell appears to have inherited his father’s gift for spectacle and showmanship, as he used Nazi imagery to provoke response and gain more attention than his organization’s numbers could otherwise achieve. In a Playboy interview, he stated outright that he was deliberately using racial epithets because they would attract more attention when it was printed — though he told (black) interviewer Alex Haley it was nothing personal. (Haley and Rockwell maintained correspondence after that until Rockwell’s own death.)

Oddly, although he and several others of his leading circle were agnostic or atheist, they claimed to be fighting for the defense of “White, Christian Civilization”: Schmaltz’s assessment is that Rockwell was trying to specify white non-Jews, and didn’t want to use “Aryan” because people confused it with the blonde with blue eyes trope. His expressed racial views were eclectic, in part because he deliberately used different approaches for different audiences: formal arguments with ‘intellectuals’, impassioned race rhetoric for the working class. This meant he could say to one room of people that of course, “most Negroes” were good people who wanted to improve themselves — while before another audience dehumanize them entirely.

As Rockwell’s career in hate was unfolding throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the civil rights movement was part of the drama — and part of his rhetoric, as he blamed Jews for promoting ‘race-mixing’. Bizarrely, he and the leader of the Black Muslim organization toyed with the idea of working together, since they were both race-nationalists who wanted the separation of blacks and whites. Rockwell personally contributed to an offering plate Malcolm X was passing around at a BM rally, and even gave tribute to the man in The Stormtrooper after his assassination. Rockwell and his group had little use for other radical right groups like the John Birch Society — and they, despite being anti-communist, understandably had no use for him, parading about in the uniforms of an enemy not twenty years defeated. (A point of trivia: Mel Brooks’ The Producers, which uses a Nazi musical as a plot point, came out in 1967. One wonders if Brooks’ lampooning of Hitler had Rockwell in mind.) Despite his contempt for much of the right, Rockwell appeared to respect William F. Buckley: after Buckley dismissed him in a National Review piece, Rockwell began writing to Buckley, leading to Buckley suggesting Rockwell meet with a priest. Rockwell did affiliate with some other groups of the period: some of his members were former Klansmen, and he toyed with the idea of using the strange Christian Identity cult — an extreme sect that believed Anglo-Saxons were the heirs of Israel and that Jews were demons — as political cover, but being an agnostic who didn’t believe in anything supernatural (besides “Destiny”) got in the way of that.

Rockwell always cautioned his followers to stay within the bounds of the law, even as he dismissed other radicals for not wanting to get physical: his preferred means of direct action was picketing events, being flamboyant, and attracting attention. During the Selma civil rights campaign, for instance, he arrived in town with plans of having one of his followers dressed in a monkey suit ambush Martin Luther King and do antics around him. Rockwell was frustrated to learn that few in Selma had any interest in assisting a self-declared Nazi: the Selma business community aired an open letter in the paper warning agitators of all stripes, from King to the Klan, to leave the town alone. Interestingly, King and Rockwell met on the city streets and had a conversation, whereupon Rockwell was invited to address the crowd at one of King’s mass meetings: the invitation was rescinded when one of Rockwell’s men punched King inside the Hotel Albert while he was registering. Rockwell believed, apparently sincerely, that racial agitation and race riots were part of a communist plot to create the downfall of the United States, but he also simultaneously believed that during an economic crisis or partial social collapse that more people would flock to his banner. Eventually, though, he was shot by an vengeful former fellower, just as his counterpart Malcolm X was.

This is not pleasant reading, given the subject matter. Being biographically-oriented, it largely focused on Rockwell, a man who threw away a happy life for hate and the pursuit of power. He and his followers, barely a hundred at any given time, are constantly scrounging for money and living in what one journalist called “a firetrap”. Their entire life was of conspiracism and antagonism. For students of the 1960’s social and intellectual currents, this may be of interest for the strange connections Rockwell had with other personalities like Malcolm X. There are occasional surprises, like Martin Luther King’s observation that race-hatred was far more intense in Chicago than anything he’d witnessed in the South. I chiefly read this because of the section set in my hometown: I try to read anything with a Selma connection, both out of personal interest and because I’m the local history librarian. On the whole, though, it’s a epithet-laden book about a man who narrowed his soul to oblivion and ultimately died for his nastiness.

Related:

Hitler’s American Friends