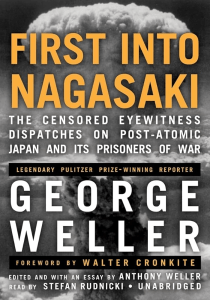

George Weller, a reporter for the Chicago Daily News, arrived in Japan only to be told that its southern islands were off-limits to reporters, dashing his hopes of being able to see what this new super-bomb had done to Nagasaki. At least….for a few minutes. After some nosing around, Weller found a soldier who was willing to get him into the city, and — there he was, days before anyone else showed up. Posing as a colonel, Weller arranged for the Japanese to give him tours of the area, including access to hospitals to talk about the mysterious disease “X” afflicting survivors — and then he began checking out the POW camps where American, British, and Chinese prisoners had been reduced to slave labor in mines and factories. Conditions were so harsh that over a quarter of all prisoners would die during the war. The stories the prisoners had to share were utterly harrowing, and they comprise most of this book, with Weller’s atomic investigations taking a back seat. The further the reader progresses, it’s easy to understand why, as witnessing the living skeletons of prisoners took precedence over idle curiosity as to how The Bomb worked. This is definitely a “graphic content” kind of book, so consider yourself forwarned.

Many Nagasaki prisoners virtually lived underground, working in mines that the Japanese had formerly abandoned as unsafe. Doesn’t matter if a cave-in kills ganjin, after all. Weller also includes other POW stories that he encountered outside of Nagasaki, including the tale of two men who evaded the Japanese for 70 days on Wake Island — collecting rainwater to drink, raiding camps for supplies, and creating a crossbow to ‘nail’ goonie birds and rats with. (Literally — nails were used as ammunition!) Most of the stories are far more miserable, though, chiefly the Death Cruise: as American forces began hammering the Philippines, the Japanese began moving POWs out of Manila, with the intent of letting them add to the slave-labor rackets . An astonishing 80% of the 1600 prisoners taken aboard the Oroyoku Maru would perish — stuffed into dark, suffocating ship’s holds like cargo, denied fresh air, water, or food, and let to fall prey to disease and madness. Twelve hundred men perished of disease, infection, or Japanese ‘discipline’ — and still others died when planes from the USS Hornet attacked the ship.

Pervasive throughout the text is the absolute vileness of the Japanese armed forces: I’ve read The Rape of Nanking and another book on Bataan, so I wasn’t surprised, but honestly after so many years the mental calluses soften and one is shell-shocked again. The cruelty comes not simply in withholding food and water, not simply abysmal conditions and constant beatings administered to weak and dying men, but the delight the armed forces took in subjecting men to such prolonged pain — making them kneel on bamboo for hours at a time, filling prisoners with water and then jumping on their stomachs. Weller charges that the Japanese had a racial superiority complex rivaling or outstripping the Germans, as they were equally cruel to Filipinos who attempted to offer even meager morsels of food to prisoners. One pregnant woman was even bayoneted and her baby ripped out of her body. As one officer informed an American pleading for more water, “We want you to die.” Some officers were willing to part with water for a price — wedding rings, for instance. One wonders why the ‘honor’-obsessed men simply didn’t shoot their prisoners rather than let them waste away and bask in their misery. There are occasional splashes of humor here — a Japanese intendant obsessed with making the prisoners play baseball, another who seriously believed lecturing ducks would counter their falling ‘production’ — prisoners were filching eggs — but by and large it is a soul-grating story of inhumanity.

This is an eye-opening but difficult-to-read book. As far as first-hand details into Japanese camps, it’s certainly effective, and unforgettable. Not for the faint of heart, though. It appears Weller filius has also edited Weller pater’s wartime writing into a larger book, Weller’s War, which I can see checking out at some point. Need something fluffy as a palate cleanser first, though.

Highlights:

A few, who had happened to be looking that way, saw the mushroom cloud climb over Hiroshima. But they had then been in the mad camp at Omuta, where an insane Japanese captain with a mania for baseball kept the diarrhea patients running bases in a lavatory league of his own.

In swaybacked or flattened skeletons of the Mitsubishi arms plants is revealed what the atom can do to steel and stone, but what the riven atom can do against human flesh and bone lies hidden in two hospitals of downtown Nagasaki.

The Japanese POW camps are one of the great omissions in World War II memory. Despite the large numbers involved—140,000 Allied prisoners through the war—they have not been portrayed in films, chronicled by historians, or officially documented as the Nazi camps have been, though they were seven times deadlier for a POW.

Murao eventually did overreach himself. He proposed that several new hospital buildings be built, and drew up plans. If carried out, his camp plans would have changed the entire coal mine into a gigantic hospital, completely girdled with ball fields. He also demanded more gloves, mitts, balls and bats. At this point the Army officers saw that they had an empire-builder on their hands, though of a peculiar order. They decided to get rid of him.

Fear was already working its way on the bowels and kidneys of the men. Asked for slop buckets, the Japanese sent them down. These buckets circulated in the utter darkness far less readily than the similar food buckets. A man could not tell what was being passed to him, food or excrement.

The second day on the tennis court the prisoners received their first meal—two tablespoonfuls of rice, raw. Their standard measure had become the canteen cup for an entire line of 52 men, and the tablespoon for each man.

It was unmistakable from the beginning that the Japanese had not lost their intention of killing their prisoners by thirst. Here was a freighter fresh from the principal harbor of Formosa, whose water tanks should have been filled to the brim. Of rice the prisoners received a one-half canteen cupful daily, but of water they received less than they would have if cast away in an open lifeboat. The ration was 2 to 4 spoonfuls daily. “If you forgave the Japanese everything else,” says one survivor, “I cannot see how you could forgive the way they denied us water all the way from Manila to Japan. Some starved, some were suffocated, some were shot by guards, some died of sunstroke, some died of cold; all things that were deliberately caused and avoidable. But everybody was thirsty, and everybody was kept thirsty all the time.”

Related:

Bataan: March of Death, Stanley Falk

Marine Combat Correspondent, Sam Stavisky. A Washington Post reporter joins the Marines and explores the Pacific Theater .

The Rape of Nanking, Iris Chang. Possibly so psychologically traumatic to the author that it led to her suicide.

“War Crimes, for God’s Sake”, 1948 Times article.

Coming up: beginning a le Guin buddy read with Cyberkitten!

Great review. Sounds like a worthwhile read, but so heavy that it’ll be some time before I could face it

Pingback: August 2024 in Review | Reading Freely

Pingback: Various & Sunday Tuesday Memes | Reading Freely