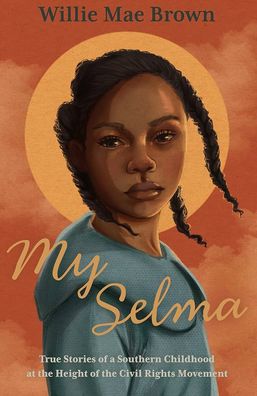

Willie Mae Brown was a child during the Civil Rights movement, which reached its high point in 1965, with the Selma to Montgomery march that resulted in the Civil Rights bill of 1965, with great assistance from the local sheriff and state troopers who gave the movement a media spectacle when it attacked the first march down Highway 80, resulting in “Bloody Sunday“. Willie Mae was not involved in the movement, being too young, but she offers here reminiscences of growing up in town during the sixties. I’ve read two other Selma memoirs during this time — one of young boy growing up in Selmont prior to the march, and of another who was an adult pharmacist working downtown. The opening chapter is a emotionally impactful and florid invocation of what growing up a young girl in the segregated south was like, complete with a description of the March 7 attack which she was absent at, and which veers into the realm of fancy, inventing dogs and robed Klansmen roaming the streets. (There were no dogs, the city authorities had as much tolerance for Klansmen as they did Yankees, and I’ve never heard or read of of Klan activity within Selma in this period or in the 1870s despite actively searching for it.) The memoir improves much as she moves to her own life, describing how her parents saved up enough money to move into a ‘white’ area of town: her father ‘Dah’ worked for the railroad and their family appears to have been relatively well to do, owning land and a rental property.

Since I knew she wasn’t involved in the movement, I read this principally for the same reason I read Ordinary Average Guy,about growing up in a trailer park in this same period: the little details of life in those days fascinate me and provide a richer view of the town that was than the politically-oriented histories. The most interesting stuff is the unexpected, like Brown recalling a neighbor woman skeeting a bit of breastmilk onto the floor before feeding a child to “calm the haint”. The majority of the book is simply these recollections of childhood, with drama between siblings and cousins happening concurrently with occasional glimpses of the casual inhumanity of the racial order — a time when the sheriff’s deputies were perfectly fine beating on the door in the middle of the night to effectively demand her father’s hunting dogs to enlist in a manhunt. Being a child who lives her life within Selma’s black community, Willie Mae is largely sheltered — but she does run into racial antagonism herself, when she begins working for a white woman who asks her for help bringing laundry into a laundromat, not thinking about the fact the laundromat owner is a hateful ass who has no compunction against hurling racial abuse at a child. The woman is embarrassed and shamed at her own naivete, and bawled out by Willie Mae’s mother as well. The timeline is a little questionable since the mood being invoked is always one of January – March 1965’s political activism and racial tension constant, with no clear idea as to when these things are happening. This is made worse to frequent mentions to “coloreds being killed”, which – well, has little connection to what was going on in Selma. The only black person killed in those months was Jimmie Lee Jackson, shot in Marion, another county over — though his death partially inspired the Selma march, so it is worth mentioning. The only man killed in Selma, in fact, was a white minister named James Reeb who was accosted and beaten, and then — oddly, very oddly – taken to Birmingham instead to Good Samaritan (the ‘black’ hospital) or the Baptist or Vaughan hospitals in Selma. (Even Montgomery would have been a better option than Birmingham, nearly two hours away!) Towards the end, young Willie Mae gets a glimpse of ‘Kang’, and sees the crowds gathering outside of Brown Chapel. Wrapping up, I’m not sure what to think of the book: it’s certainly well-written, prose wise, and I suppose if you were absolutely ignorant about racial relations in the 1960s it would be eye-opening. The book make depressingly clear to me how prejudice begets prejudice — Willie Mae and her contemporaries have the same contempt for poor white ‘crackers’ that the latter have for them, regardless of their actions — the only difference being these two communities of prejudice being that poor blacks weren’t in a position to participant in bullying. Power or no power, though, racism poisons the soul, and it’s sad to see this made manifest but not reflected on.

Pingback: January 2024 in Review | Reading Freely