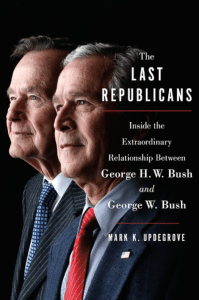

I was interested in reading this book even before my unexpected presidential reading tangent of this last month, in part because of my age: George H.W. Bush was the first president I remember, and holds that title somewhat fixedly in my brain: he is The President just as John Paul II is The Pope, and Elizabeth is The Queen. I came of age during his son’s administration, voting for him in 2004 and then (as I began developing ideas about politics independent of my parents and culture) becoming sharply critical of the expanding police state and the unending war in the middle east: to him I owe both my standing interest in geopolitics and my often strident libertarianism. A joint biography of these two men is somewhat special for me, then, unavoidably saturated with nostalgia from these two formative periods in my life, and the tension that comes from confronting that nostalgia with my adult perspective. It’s an unusual book because of the dual nature of its subject, and their unique relationship: while John Adams was alive to see his son John Quincy take office, he was in his last years during office and could never advise his young scion. Bush paterfamilias and George W., though, were intimately involved in one another’s political lives from the moment H.W. began earnestly seeking an elected office.

The Last Republicans is the story of a unique father and son, whose fraternal bond was made stronger by politics far before Bush the younger ran for office in 2000. Bush senior made history when he became the first vice president to be elected to the presidency since Martin van Buren, and further made history when he saw his son later follow him in office, which had not be done since John Adams’ son John Quincy became the sixth president. Although my grumpy libertarian side would like to dislike George H.W. Bush for his CIA tenure, I’ve never been able to manage it — and I was relieved to learn here that he had no long connection to that organization of spies, coup-installers, and general murderous mischief-makers, but was simply appointed to the top post by President Ford — a bit of a consolation prize for not being asked to join Jerry’s ticket as the vice presidential nominee. George H.W had a difficult time in the Republican party in the late sixties and seventies, as conservatism itself began changing — becoming more militant in response to both Soviet expansion and LBJ’s Great Society, and advancing the fortunes of men like Barry Goldwater, who were not from the respectable Taft-Bush sort of conservatism. The rising neo-cons looked askance at Bush’s breeding, but as I discovered here, he was no mere manor-born son of privilege. He and his wife were azure-blooded, to be sure, but set forth to make their own lives in Texas, where no one cared about their names — raising their small family in modest circumstances. Although Bush would eventually make a fortune in the oil business after learning the ropes as a clerk, he was not content to rest on his laurels and join the boys for cigars and brandy at the club: he was an aristocrat in the Adams-Washington sense, believing strongly in the need to serve the common good. This led him to politics and congressional runs, where his son George — rapidly nearing adulthood — watched and helped his father. Ultimately, Bush senior’s regard in D.C. would grow as a result of appointments (as UN Ambassador, CIA director, etc) before launching him onto the national spotlight alongside Ronald Reagan.

One striking aspect of The Last Republicans is how deeply the Bush children dote on their father: even as they matured into men and women of importance and prominence, they looked on him as a near-demigod. When George W. in his younger years was partying and getting into trouble, all it took from his father was a Look to put the fear of God into him. (George wouldn’t give up the drink entirely until his father began moving deeper into politics: although he’d known he needed to for a while, it was fear of embarrassing his father that really did the trick.) George W. did not have his father’s early drive and motivation: by Updegrove’s account, though he drifted between the worlds of business and politics. As a kid, he dreamt of playing baseball and flying planes, the latter like his father. He ran for office early, and lost (as did his father), but continued to enjoy the challenge and promise of politics despite despising D.C. itself. George W. had an interesting, almost paradoxical realationship with the east coast elite: raised in Texas, he was “more y’all than Yale”, self-conscious and proud about his rural beginning. At the same time, though, he was aware of and accepted his family’s privileged roots — and looked askance at those who were embarrassed about theirs. It was during his father’s presidential runs that George W. committed to politics, pursuing the governorship of Texas and putting him on a path to challenge Al Gore for the presidency in 2000.

As Updegrove tells these men’s stories, he comes back time and again to their father-son relationship. The Bush family was especially devoted to one another because of the death of George’s sister Robin, and her dying goodbye to her family — “I love you more than tongue can tell” — became a refrain when the Bushes were consoling one another, or were facing dire straits like when H.W. was effectively on his deathbed from pneumonia. W’s close attachment to his father only strengthened when he joined the elder Bush on the campaign trail, and their bond increased even further when George W. became president. That office is a responsibility and weight that only other presidents can understand, and the Bushes shared a similar problem with Saddam Hussein, though in W’s case it was more of a potential threat that took on false weight because of the 9/11 environment. (Updegrove uses Hussein merely as a stock villain and does not mention that DC supported his war against Iran throughout the 1980s, which is part of the reason Hussein thought he could get away with invading Kuwait.) George H.W. was, like his son, prepared to rout Hussein’s forces without congressional approval if need be — contra the usual story that H.W. was prudent and his son was impetuous and reckless. Updegrove’s account gives a good impression of how deeply both men sat with the choice to wage war — in George W.’s case, twiceover, and living with the responsibilities when it was revealed that DC’s intelligentsia had mislead the state into war on false pretenses. Though sharing similar burdens and sometimes differing in policy, George H.W. chiefly counseled his son as a father — not giving him advice as a former president, but offering him unwavering emotional support and an open ear.

The Last Republicans is a moving account of their bond, but as its title indicates, it’s not just about the Bushes. Trump is in the the background, always, and Updegrove points out that Trump has been entertaining the political arena for decades, and with a consistent message, and the point of the book is fairly clear: the Bushes were each different kinds of conservatives, George W. being closer to the Goldwater-esque brand that emerged in his youth, but they were in line with the Republican party over the years: they supported DC’s institutions and served as best they could with principle and compassion, believing and working towards the future — a view Updegrove contrasts against Trump’s “dystopian” vision. Updegrove appears to believe that just as the Republican party changed from Bush to Bush that it is continuing to evolve into a party dominated by the more populist nationalism that Trump has consistently championed since the eighties. Populism is an everpresent source of political activity in the United States, sometimes sparking into a roaring fire and then dying away — and while I’m tempted to say that the current populist wave will do that, it’s certainly persisting longer and creating more long-term effects, like the continuing pushback against foreign adventurism. The book ends with an interesting little look at George P. Bush, sometimes considered the next Bush with a bright future in politics, and who is alone among his family in supporting some of Trump’s policies. Although I would have preferred the focus of this book stay properly on the Bushes instead of the author trying to make a political point, they do maintain center stage until the very end. Updegrove’s frequent attempts to insert Trump, some skimming of context, and one fantastically bad misquote* drag down what is otherwise a really good book.

[*] Updegrove has Bush calling Putin on 9/11 to tell him he had better not try to use this as an excuse to declare war on the United States. Not only is this transparently absurd, but if one actually looks for the Andy Card remark this is based on, it’s nothing like that at all.

Coming up: Five Months on Mir, plus more Bush and Biden. I’ve just finished My Name is Asher Lev (what a novel!) but am thinking of posting its review along with a couple of others as part of a Jewish Literature series.

The misquote makes me think someone should take a close look at everything the author shared. Thank you for this thorough review.

You’re welcome! One of the benefits of reading a bunch of these books around the same time is being able to compare stories & facts while they are fresh.