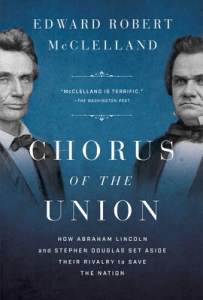

Before the last month or so, my awareness of Stephen Douglas was that he had sparred against Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln-Douglas debates. I did not realize until reading 1858 that these debates were not part of the 1860 presidential election, but were instead part of a Senate race. Douglas would win, but their very public debates gave Lincoln a larger stage — and they would be part of the wind that bore him towards Washington, along with Douglas’ inability to keep his increasingly polarized party on the same track. When Douglas learned that Lincoln had beaten him in the presidential race, he said — “I must go South.” Not because he wished to join the southern democrats in seceding, but to try to argue them out of it. In retrospect, that seems like a doomed mission: the South arrived at its Democratic convention spoiling for a split with their northern brothers — first in the party, and then in the union. “Three cheers for the Independent Southern Republic!”, they cried as they walked out of the convention hall and paraded down the street into another hotel. Chorus of the Union is a deep dive into Lincoln and Douglas’ history, and how (two-thirds of the way in) Douglas put his own politics aside in a last-ditch effort to prevent the breakup of the union and the possibility of civil war.

Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln both made their political fortunes in Illinois, but were not native sons of the west; Douglas came west from Vermont, and Lincoln’s family from Kentucky — but they were part of a third generation in American politicians, and followed closely on the heels of prominent westerners like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. The two knew each other from their young adult days, debating politics in the back rooms of stores — but Douglas sought political office and won great acclaim, while Lincoln served for a brief time to return to working as a lawyer. Interestingly, it was the one who made the other’s career. Lawyer Lincoln, raised by anti-slavery Baptists and deeply bothered by his few encounters with slave parties being transported along the river, was resolutely against the institution, and when Douglas championed an act — the Kansas-Nebraska act — that would effectively allow for its continued expansion, Lincoln rejoined politics as an active campaigner. The two would run against one another in 1860, but Douglas would be running against the disintegrating factions of his own party to boot. “The Democracy” had split first into northern and southern parties, and then into still other groups, to the effect that Lincoln would ultimately win despite only claiming 39% of the popular vote. After Douglas realized his candidacy was lost, he journeyed into the South hoping to argue against secession — and, McClelland marks, he took that danger far more seriously than the Republicans themselves. Lincoln and Douglas had made their careers in Illinois, a place that was divided itself between commercial and agricultural interests: Illinois’s southern third was commonly called Egypt for its rich river deltas that had attracted plantation culture early in its history. Both men were used to having to balance competing interests — but Douglas, unlike Lincoln, knew how ornery southerners could be.

The resulting third goes a long way to redeeming Douglas, I think. For most of the book, it is extremely easy to sort the two men into two very different buckets. Lincoln is the pragmatic idealist who hates slavery on moral grounds, is determinedly hopeful that it will die, but acknowledges that it cannot be done within the grounds of political reality. Douglas, however, is politics first: he may dislike slavery in an abstract way, but didn’t truly care about it one way or another. His focus was on maintaining the Democratic party — or The Democracy, as it was often known at this time — despite the fire and fury of abolitionists and secessionists alike. After the election, that shifted naturally to a fervent desire to maintain the Union. Douglas in this moment is not playing politics; he is traveling, arguing, and contending for his country, in a way that pushes him nearer to self-sacrifice than readers have yet seen. In his visits South, he denounced Lincoln and all the Republican party stood for, but maintained that the election of any one man could not justify the destruction of the Union. The Constitution itself, the powers of the States, would diminish Lincoln’s ability to act even if he entered office with a mission against the South. The South’s chances of preserving its interests are greater inside the Union than out, he said — and this proved to be true, since Northern states passed a great many laws (from intense protective tariffs and infrastructure bills to playing around with fiat currency) that would have never passed a Congress in which Southern states had a voice. Amusingly, while in Nashville Douglas crossed paths with the arch-fire eater Yancey, who had just been visiting the North to dissuade them from voting Lincoln! Douglas ventured even into Montgomery, Alabama, Yancey’s stomping grounds and the first home of the southern Confederacy: there, his carriage was pelted with eggs, though he did give a speech before departing downriver to Selma. He returned to Washington to help argue for legislation that might pacify the fears of the South, though nothing was able to be passed before Congress’s session ended. After the war began in earnest, Douglas traveled through the north, admonishing his fellow citizens to rally around the president — and in the summer of 1861, his health spent in his impassioned pleas to Americans north and south, he died in his hotel room while still on the mission.

This was quite the book. I’d gotten into it because I was intrigued by the notion of Douglas standing by his former opponent. This is not that unusual in politics — John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay both backed Jackson against the French when they were being obnoxious deadbeats, and those dons hated Old Hickory — but given the stakes involved I wanted to read more about it. Having read a few other books in this subject in the last few months made the revisit somewhat laborious at first — especially the level of detail that McClelland gets into with the Debates — but seeing Douglas really come into his own in the last third made the march worth it. This is also as close as I’ve gotten (so far) to a proper biography of Lincoln, though one will follow this, and it made me more appreciative of Lincoln’s gift for humor — though his constant jokes about Douglas’ height make him seem a little mean-spirited at times. What I liked most about it beyond Douglas rising to the occasion beyond the pettiness of party politics was getting a rare look into political goings-on during the “secession winter” in which the US government as it stood, and Lincoln’s slowly-forming team, pondered what course to take following South Carolina & company’s decision to start singing a new descant. This is slightly wonkish at times, but serious students of the period will delight in the detail, and more casual ones can still endure given McClelland’s accessible writing style.

Quotations

“You can’t overturn a pyramid, but you can undermine it,” Lincoln told

Locke, “that’s what I have been trying to do.”Lincoln was not yet Douglas’s equal as a political operator, but the debates had proven he was Douglas’s intellectual superior. Lincoln was better read, for one thing. Not only had he read more widely than Douglas, he knew how to read. When Douglas studied history—as he had done for the first time while researching the Harper’s essay—he sought only to validate his own beliefs.

“The gentleman forgets to tell the ladies that he is a bachelor,” Thomas Craig of Missouri ribbed Cochrane. The proceedings broke up for several minutes, as the entire hall burst into laughter. “I was about to inform the ladies,” Cochrane said, attempting to defend himself. Craig had another riposte ready. “Oh, no matter! There is no need to volunteer the announcement, for the looks of the gentleman are a sufficient guarantee that he has not been, and never can become a married man.”

“Mr. Lincoln is the next president,” Douglas told his secretary, James B. Sheridan. “We must try to save the Union. I will go south.”

“I reply that if they elect Mr. Lincoln, on their heads rests the responsibility,” Douglas blustered. “No man on Earth has exerted his energies so much to defeat Lincoln’s election as I have. No man on Earth would regret his election more than I would. I regard him as the head of a party, the whole principles of which are subversive of the Constitution and the Union. I would regard his election as a great public calamity, but not as a cause of breaking up this government. e election of no man on Earth by the people, according to the Constitution, is a cause of breaking up this government.”

As Lincoln held court, in an armchair too commodious for even his gangly frame, a visitor from New York asked whether the South would secede if he were elected. “They might make a little stir about it before,” Lincoln said, still uncomprehending of the passion his candidacy had aroused in the South, “but if they wait until after the inauguration and for some overt act, they will wait all their lives.”

While Douglas’s support was broader than any candidate’s, nowhere was it as deep. In 1860, the electorate was polarized between Northerners who wanted to stop the spread of slavery and Southerners who demanded its expansion. Douglas, who based his campaign on the principle that the federal government should not take either side, was rejected by majorities in both sections.

“It is not of your professions we complain,” James Seddon told Lincoln. “It is of your sins of omission—of your failure to enforce the laws—to suppress your John Browns and your Garrisons, who preach insurrection and make war upon our property!”

“I believe John Brown was hung and Mr. Garrison imprisoned,” Lincoln retorted.“Civil war must now come,” the Richmond Enquirer editorialized the morning after. “Sectional war, declared by Mr. Lincoln, waits only the signal gun from the insulted Southern Confederacy, to light its horrid fires along the borders of Virginia.”

Pingback: January 2026 in Review | Reading Freely