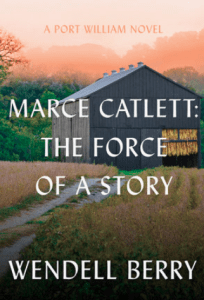

Marce Catlett The Force of a Story takes a life we’ve visited with previously and then visits with it for a while, learning how the story of Andy Catlett was really a continuation of a story in which his grandfather Marce and his father Wheeler had been swept up in prior. This is a theme in Berry’s writings, really: “there’s always more to tell than can be told.” Readers who have delved into the Port William series know that no matter how stirring one particular story within it, the story always grows in richness when other Port William stories are read alongside it, for we begin learning the history of these people and their town. Marce Catlett goes for that effect in a single volume, as we follow the plight of independent farmers from the turn of the 20th century to the time of Andy Catlett, a man whose life has previously been used to shine a light on the community’s ‘dismemberment’. We already know that Andy goes to college and begins to learn of ‘modern agriculture’, only to walk away in disgust after realizing its methods are divorced from the land and particular the love of it – bearing more resemblance to industrialism than stewardship and husbandry. Marce Catlett goes a bit deeper, though, taking us back to a day in 1907 where a man’s entire year of labor, care, and pain disappeared at the auction-house – prices driven so low by one buyer eating up all the others that the crop appears to have not been worth planting at all. This connects to the later theme of Port William books – the brutalization of farming and of towns like Port William by those whose only motivation is the efficient ‘use’ of land, not its care. This was like many Port William stories, beautiful, tragic, and humane. Unusually, though, towards the end it slides into what sounds like one of Berry’s many essays, but one lightly illustrated by Andy, Wheeler, and Marce’s lives.

So in their memories the way went: a passage through the dark, undertaken familiarly by men of their kind in their time. So Marce remembered it to Wheeler, who told it to Andy, who in a world radically changed needed a long time and great care to imagine what he heard, but as he has imagined it he has passed it on to his children, for the story has been, as it stil is, a force and light in their place.

“[Hers] was an old mind, as he would come to understand. It was contemporary insofar as it had acquired the knowledge of younger people, but it was also continuous with minds that had come and gone long before hers.

For [Marce], morality began with a mortal fear of the waste of daylight, particularly of the morning light. He believed with the passion of old custom and his own long observance that at four o’clock in the morning, a man should be awake, on his feet, and at athe barn, caring for what needed care, feeding what needed to be fed.

In those days nobody knew he was a boy who belonged to a story. In those days he did not know it himself.

Port William’s fatal mistake was its failure to value itself at the rate of its affection for itself. Gradually it had learned to value itself as outsiders — as the nation — valued it: as a ‘nowhere place’, a place at the end of the wrong direction. So far as Andy has learned, the Old Order Amish, alone in all the country, have had the wisdom – the divine wisdom, it may be — to give to their own communities a value always primary and preserved by themselves.

As people have grown helpless and lonely, they have come to be governed by those most wealthy, who rule by the purchase of nominal representatives, who, having no longer the use of their own minds, do not know and cannot imagine the actual country by the ruin of which they and their constituents actually live.

Pingback: What I Read in 2025 | Reading Freely