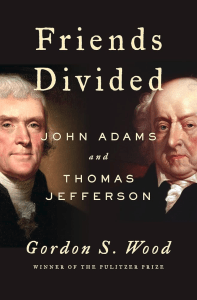

When I first read Gordon S. Wood, his Revolutionary Characters annoyed me in its short shrift given John Adams. Adams was one of the earliest voices inveighing against Parliament’s abuses of the American colonies, and I was flabbergasted that he was shoved to the back of the book along with a knave like Aaron Burr. In Friends Divided, he gets the attention he merits, alongside his friend and sometimes rival Thomas Jefferson. This is a double character study that explores not simply the rupture in their friendship that saw an eleven-year silence between them, but their differing views as they evolved throughout the men’s multi-decade friendship and political partnership. The book is wonderful in giving a fair notion as to how complex the minds and character were of these two men; he does not try to box and label them up, but draws heavily on their own writing (manuscripts and letters) to allow them to speak for themselves. While I was already familiar with the course of Adams and Jefferson’s friendship via Joseph Ellis, this goes into more detail and proved one of my favorite reads of this year.

Adams and Jefferson, despite their early working relationship and friendship, were two very different men. They hailed from two very different colonies, and from within different classes within those colonies. Adams came from fairly humble stock, that of a yeoman farmer whose hard and humble work had made it possible to send his boy to school – -even if the young John Adams was perfectly content at being a farmer. All Adams could boast of was his ability and desire to work, and in his studies of law and history he would be among the elite of the founding generation’s intellectuals. He was an absolute workhorse as an attorney, building a successful practice for himself before Parliament’s abuses of the colonies drove him into politics. Jefferson, on the other hand, came from more rarefied stock, and he was partially raised by relatives whose blood ran even more blue. Whereas Adams came from a rough & tumble world, Jefferson was manor-born, raised in grace and civility — at least, in the manor, removed as it was from his fields where slaves raised tobacco. Perhaps their disparate backgrounds contributed to their differing casts of mind: Adams was realistic to the point of cynical, believing people were inherently flawed and that progress could only ever be a tentative thing. Jefferson was more of an Enlightenment idealist, believing humanity could flower were institutions like government and organized religion in the way, and seeing America was the perfect place to see the next steps of humanity.

Friends Divided follows the two men’s lives through their becoming friends amid the Revolution, and their service to the early Republic. It was there, when principles met power, that the two began to grow apart. Although Adams and Jefferson had both gone to law school, it was Adams who lived, breathed, and had his very being within the law. It was the law — the English common law — that gave Adams his name and what success he had created for himself in the world, and he took it far more seriously than Jefferson, who was more more fascinated by architecture and making his home — food and servants included — as French as possible. For Adams, law was the thing that made civilization at all possible, and he not only admired the English legal constitution, he despised the actions of those like the French revolutionaries who would burn the world down to try to recreate it a new image. (He had similar views on religion, despite being more of a Unitarian, he regarded religion as fundamental element of society and his appreciation for Christianity grew with the years..) Adams correctly predicted the revolution would end in bloodshed and disaster, and his and Jefferson’s differing attitudes toward their English heritage and the”promise of the French revolution” not only led to arguments but political issues as they both served as President during the French revolution’s aftermath and the rise of l’emperour. This divide between English sympathies and French sympathies was not limited to these two men: there were armed mobs fighting each other in the capital, and a surge of French immigrants made the tension even thicker and more volatile. While Adams thought Jefferson and his compatriots’ wilful bindness as to the revolution’s bloodlust was mad, Jefferson thought Adams’ own attachment to the nation they’d thrown off political ties to — and his working with arch-Federalists like Hamilton who wanted a far more centralized and potent nation-state than either man would be comfortable with — was similarly naive. (Of course, whereas Jefferson was the leader of the “Republicans”, Adams was disliked by the Hamiltonian Federalists as well for being too sympathetic to Jefferson!) Bickering between the two of them would entail a long silence after Adams’ departure from the Federal City.

In the last few chapters, Wood looks at the successful efforts of Dr. Benjamin Rush to reunite the old friends, and this is honestly enjoyable because the reader is allowed to experience the men as men. Adams, fires off letter after letter, gabbing about whatever he’s been reading and thinking, often being facetious and trying to get a rise out of Jefferson. Jefferson, for his part, had far more celebrity status and couldn’t write as much to Adams (having many other people to write to, so much so that he dreaded the arrival of the post), but was responsive. As the larger anniversaries of the Declaration approached, Adams wryly noted that he was suddenly getting more invitations to join societies and the like, as the men of the Second Continental Congress were being pushed into sainthood. Woods notes that while Adams’ view of government was likely more accurate in the long-term , there is a reason that Jefferson’s name lives where Adams’ has only lately been recovered by the efforts of David McCullough. While Adams said things people do need to hear, Jefferson said things that inspired people to be more – and his view of America as a transcendental nation was far more able to cope with the nation the Thirteen United States grew into, with varying ethnicities and religions than Adams’ stricter view that tied it to its English legal heritage.

There is a great deal more in this book than could ever be packed into a simple review as this one. I was much impressed by it, enjoying the narrative as well as the diverse details, the long study of these extraordinary men’s lives. I’ll definitely be reading more Wood.

Quotes and Highlights (I read from both the physical and kindle versions):

But despite all that the two patriot leaders shared and experienced together—and the many things they had in common are impressive—they remained divided in almost every fundamental way: in temperament, in their ideas of government, in their assumptions about human nature, in their notions of society, in their attitude toward religion, in their conception of America, indeed, in every single thing that mattered. Indeed, no two men who claimed to be friends were divided on so many crucial matters as Adams and Jefferson. What follows is the story of that divided friendship.

“How could any Man judge,” wrote Adams in 1761, “unless his Mind had been opened and enlarged by reading.”

Jefferson’s ability to play the violin may have been more important to his courtship than a coat of arms. A story passed down through the family had two rival suitors arriving at Martha Wayles Skelton’s house at the same time. Ushered into the hall, the two men heard from an adjoining room the young widow’s harpsichord and soprano voice blending with Jefferson’s violin and tenor voice in wonderful harmony. After listening for a stanza or two, the two suitors, realizing what they were up against, took their hats and retired, never to return.

Adams tended to be more frank and honest in displaying his feelings. No one in the Congress had any doubts where he stood, and no one did more to move the delegates toward independence. Adams, Jefferson later told Daniel Webster, “was our Colossus on the floor” of the Congress. He was “not graceful, not elegant, not always fluent.” But, said Jefferson, Adams in debate could come out “with a power, both of thought and of expression which moved us from our seats.”

Adams, alive and sensitive as he was to the world around him, soaked up as much of Philadelphia as he could. He was especially impressed by the number of different churches in the city, and each Sunday he went to two or three services in order to experience nearly all of them: Anglican, Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian, Quaker, German Moravian, and Roman Catholic. He had never been in a Catholic cathedral before, and that experience, as he reported to Abigail, revealed not only his extraordinary sensuousness but also his religious sensibility.

ADAMS’S EXPERIENCE IN EUROPE was different from Jefferson’s. For Jefferson the luxury and sophistication of Europe only made American simplicity and virtue appear dearer, while for Adams Europe represented what America was fast becoming—a society consumed by luxury and vice and fundamentally riven by a struggle between rich and poor, gentlemen and commoners.

“Reasoning has been all lost. Passion, Prejudice, Interest, Necessity has governed, and will govern, and a Century must roll away before any permanent and quiet System will be established.”

Both men enjoyed showing off their wide knowledge of Greek, Latin, and modern literature. Indeed, their letters often exploded with kaleidoscopic displays of learning in classical and Christian texts that are bound to leave a modern reader thoroughly abashed. At age seventy-five, Jefferson offered a long disquisition on the difference between the pronunciation of ancient and modern Greek, followed by a learned discussion of the changes in the pronunciation of American English. For his part Adams once mentioned Archytas, the fourth-century BC Greek philosopher, and followed that up by pointing out that “John Gram a learned and honourable Dane has given a handsome Edition of his Works with a latin translation and an ample Account of his Life and Writings.”

Adams said he considered Jefferson to be as good a Christian as Priestley. But that was not much of a compliment, since Adams later went out of his way to disparage Priestley “as absurd inconsistent, credulous and incomprehensible as Athanasius” and no different from all those other so-called “rational Creatures,” the utopian French philosophes.

It was a good thing for judges to be independent of a king, but it was a gross error to make them independent of “the will of the nation.”

“Public Virtue is no longer to Rule: but Ambition is to govern the Country…..Call it Vanity or what you will,” but Adams believed his and Washington’s administrations were the last expressions of selfless disinterested government. In the future, all the American people could hope for was that they might “be governed by honorable, not criminal, ambition.”

According to Quincy, Adams actually looked forward to his death, when like Cicero he would meet up with all those he had known. “Nothing,” he said, “would tempt me to go back” and relive his life, which was what Jefferson was willing to do. “I agree with my old friend, Dr. Franklin, who used to say on this subject, ‘We are all invited to a great entertainment. Your carriage comes first to the door; but we shall all meet there.’” If Franklin had become his “old friend,” then Adams had indeed mellowed.

Sounds like an interesting read! I’m imagining these attention seeking letters, wanting to read more 😂

I think I have a copy of the Adams-Jefferson letters on my kindle. 🙂