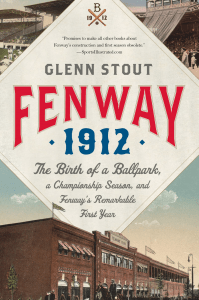

Fenway Park in Boston is the oldest continually operating major-league ballpark in the United States, and has developed into a character or an attraction in its own right for that reason. Fenway has not lasted as long as it has by being change-resistant, Glenn Stouts offers: instead, it has continually altered itself so much so that save for the outside ticket-office facade, the Fenway of 1912 would be unrecognizable to current-day fans. Fenway 1912 is a history of the ballpark’s creation, its hurried opening for the 1912 baseball season, and of that year Red Sox team’s storied World Series bid.

The season was marked by two exciting events: the rise of Smokey Joe Wood, who became a record-setting pitcher and was regarded as the best in baseball after his pitching duel with Walter Johnson; and of course, the World Series run, which was split between Fenway and the New York Giants’ Polo Grounds. Both events forced park changes: the pitching duel attracted so many spectators that they filled the seats, the grass, and then began spilling into the field itself, even encroaching upon the field of play before policemen intervened. (They took over the dugouts, leaving the players to sit on the field like schoolboys waiting for their turn at bat!) It is thought that some 40,000 people were present at that game, something remarkable when the reader realizes that modern Fenway can accommodate that number, but only after a century of finding ways to add more seats – like seating people on top of the Green Monster, the legendary left-field wall. More wooden bleaches were added for subsequent games and the World Series, but even so the ballpark was so jammed that the Red Sox’ unofficial fanclub, the Royal Rooters, were denied places to sit after arriving late – despite having tickets- – and nearly created a brawl.(Not surprisingly, the Red Sox’ other World Series games in the 1910s often happened at the larger Braves Field.) The world series itself was exciting, marked by a game declared a tie – it became too dark to see – and several shifts in momentum between the Red Sox and Giants as it wore on. The alterations changed the overall shape of the field, creating more quirks and substantially altering several plays.

Stout ends the book with a brief history of Fenway since, and points out that Fenway did not become The Fenway, a park with significant sentimental power over its Fenway faithful, until the 1970s or so. This was around the same time that the left field wall became known as the Green Monster. Perhaps the destruction of places like Ebbetts Field and the Polo Grounds in the 1960s prompted more attention on Fenway’s historic status? Whatever the reason, Fenway survives — even though its seats are the most expensive in the MLB.

Although it has become a cliché to make the claim that Fenway Park is still recognizable today as the same park that opened in 1912, that is true only in the most limited sense. If a contemporary Red Sox fan were somehow sent back in time and deposited in Fenway Park on April 9, 1912, it is unlikely that any but the most knowledgeable rooter would recognize it at all. For while Fenway Park still occupies the same basic footprint today as it did in 1912, virtually every other notable structure and feature of the ballpark has been removed, recast, renovated, or otherwise changed.

Fenway has survived not because it has been preserved in the original, but because it has not been preserved, because until quite recently it was never treated as special enough to preserve, and because the ball club has rarely hesitated to make practical changes to extend its useful life.

At the reception at the bride’s home the guests were entertained by the Red Sox Quartet, a barbershop singing group made up of Buck O’Brien, first baseman Hugh Bradley, and pitchers Marty McHale and minor leaguer Bill Lyons, who were filling in for occasional tenor Larry Gardner, already back home to Vermont. Later that fall the quartet played the New England vaudeville circuit, including B. F. Keith’s theater in Boston, where a receptive reviewer noted that “if they wish to foreswear baseball as a livelihood there is a rosy career awaiting them as singers.”

As Wood toed the rubber Cobb danced off first, feinting toward second again and again. A flustered Wood threw to first base over and over, a little harder each time, getting more distracted and angrier by the second. When Cobb finally took off Wood was so disconcerted that he never even threw the ball but watched helplessly as Cobb took second unimpeded.

Just before the ticket office opened at 9:00 a.m., the line stretched some twenty blocks—nearly two miles—down Eighth Avenue to 155th Street, then down Broadway to 145th, then on Edgecombe to 138th Street.

Nearly three hundred baseball writers were ensconced at the Hotel Imperial. Over the past twenty-four hours they had discovered that in order to get an interview, as the New York Tribune reported, “some of the long green has to be flashed.” The going rate was $2 a word. Even Christy Mathewson refused to part his lips unless paid to do so. It was cheaper for the writers to make the quotes up, and many did.

When the gates opened shortly after noon the crowd spilled into the Polo Grounds in a flood. News that war had broken out in the Balkans drew only disinterested shrugs—fans were far more concerned about the impending war between the Red Sox and Giants than a conflict halfway around the world.

Boston’s best hope for vanquishing the Giants and winning the World’s Series came down to only one man, Joe Wood. If Wood could pitch in October the way he had pitched from April through September, it did not matter at all who the Giants pitched opposite him, or even who Wood faced. Wood, at his best, was the best. It was that simple.

As the players hurriedly dressed and rushed to South Station to catch the Gilt Edge Express to New York, the two clubs, both exhausted but one also exhilarated and the other exasperated, were spent. They had just played three games in which every pitch in every inning had mattered and in which the fortunes of both teams had swung back and forth so many times that fans had nearly gotten whiplash just from watching.