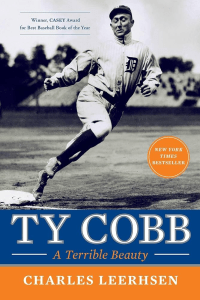

I’ve known the name Ty Cobb since I was a kid: baseball is an anomaly in that it’s the only sport I’ve ever cared enough to read about, both as a boy and now in my dotage. I encountered Cobb early, along with Cy Young and Babe Ruth, and I think his status as a Georgia boy locked him in as a favorite, despite – or perhaps because of – his pugnaciousness. A researcher doesn’t have to dip very far into papers to find Cobb getting into fights on the field, or going into Achilles-in-his-tent mode because of some foolish act on his manager’s part. Whatever his flaws, though, in the latter half of the 20th century Cobb was turned by the popular ‘mind’ and mythmaking sportswriters into an absolute monster – a literal killer, a vicious racist who couldn’t see a black man on the street without flying into a murderous rage, a man who filed his spikes and separated fielders from their limbs every game. Although Cobb’s short temper had already resulted in a Cobbiracture in his own lifetime, his infamy today largely owes to the lies, damned lies, and half-truths invented and perpetuated by Al Schmuck, a third-string sportswriter who was haphazardly assigned to help Cobb compose his memoirs in his dying days. Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty is both a full appraisal of the real man – his virtues and vices – and a long-overdue takedown of Schmuck’s literary dribblings.

Ty Cobb is a legend in baseball history, the first man to be inaugurated into the Baseball Hall of Fame – by near-unanimous decision. He was also one of the first baseball players to become a media personality – a celebrity, in other words, and navigating that novel challenge would mark his early career. Cobb was born in rural Georgia, and was neither a redneck nor a patrician, though arguably closer to the latter. His mother’s “people” owned land, and his father was very respectable middle-class, active in the newspaper business as well as state and local politics. Young “Tyrus” was obsessed with baseball and already possessed a wicked temper at an early age, and when he began pursuing professional ball in nearby Royston, it was largely because his father was tired of arguing with him about it and figured a season of that life would get the bug out of his system. Instead, Cobb’s obsession and energy opened a door to the Detroit Tigers, where he would play ball for the majority of his professional career.

Key to understanding Cobb’s approach to baseball, and his success in the ‘field’ (so to speak), is that he played during the ‘dead ball’ era where homers were oddities and the mainstay was ‘inside baseball’. Not only were the balls themselves constructed differently from later Spaldings – with rubber cores and looser strings – but there were far fewer rules applied to them. Balls got dirty, soft, and unpredictable – and they were used for most of the game, unlike today when over a hundred balls a game are discarded – usually, given to fans. Most of the action took place in the infield, and psychology and strategy played larger roles than Babe and Ted Williams swinging for the fences. Cobb excelled at this aspect of the game, using his natural aggression to create ‘mental hazard’ for the opposition. (One wonders if he ever had Nathan Bedford Forrest’s “put the skeer in `em” in mind.) One author likened Cobb to compressed steam: he was always writhing, pushing, scheming. The pushing is literal: he used to give the plate-bags little kicks to aid and abet his base-stealing, scooching them closer to the next base.) Cobb resented references to ‘natural talent’: his success in baseball owed to constant work and thought. When he began with the Tigers, the other players showed up drunk or hungover: Cobb spent his evenings reading and thinking – thinking about how to use other fielders’ reflexes against them. Although the threat of physical aggression was certainly part of creating ‘mental hazard’, Leehrsen writes that Cobb’s variety of base slides were largely oriented towards avoiding contact with the baseman. This wasn’t because Cobb didn’t want to hurt anyone (his quick fuse and frequent fighting put the lie to that!) but because avoiding contact was the obvious way to avoid being tagged out. The famous photo that portrays Cobb evidently sliding into base with his legs poised to deliver a groin kick to the unhappy fielder is a quirk of perspective: in reality, the baseman offered, Cobb was kicking the ball out of his hand. (The two immediately got into a fight and were both fined.)

Although Cobb’s reputation for violence was definitely not unwarranted — whatever quick temper he had was made far worse by the prolonged and aggressive hazing he was subjected to during his second year on the Tigers — he was not the monster the newsmen made of him in his own lifetime, let alone after he died and his legacy was left undefended against the manipulations of opportunistic hacks like Schmuck. In the TV show I’ve Got A Secret, contestants kid Cobb about sharpening his spikes, which he takes with the face of a man who has heard this a thousand times before. Cobb said in interviews that his cleats hit other players maybe three times in his career, and he’s on record as advocating for officials to inspect players’ spikes prior to games. A lot of stories about Cobb’s violence — including three homocides — are completely made up, or in the case of his confrontations with hotel staff, deliberately given racially charged light. If Cobb were the violent racist he was alleged to be, it seems strange that he was a vocal advocate for integrating the major leagues, attended Negro League ballgames, and had such a warm relationship with his black valet that the man named his child after Cobb. Although I knew a bit about Cobb’s life — broad outlines, anyway — I appreciated the amount of non-baseball information here, including Cobb’s active reading life. He always appeared to be in the middle of two books, with a special fondness for titles about Napoleon, and even though he was concerned reading would ruin his eyes, he couldn’t keep himself away from the page. There were a lot of suprises, like how when Cobb was just starting out with the Tigers, how he would spend the offseason performing on stage. Evidently, his psych-out tactics in the ballpark had some dramatic roots that flowered differently on the stage.

Although Ty Cobb is the star here, A Terrible Beauty frequently mentions the exaggerations and outright fabrications of Al Schmuck, who Doubleday picked to assist the aging and dying Cobb in creating his memoirs. What Doubleday didn’t know, or ignored, was the fact that Schmuck was such a lazy and sloppy writer that several institutions — including the Readers’ Digest — would refuse his pieces outright. Schmuck’s books are riddled with factual inaccuracies, some so significant that one wonders how he had the gall to call himself a sportswriter. A Terrible Beauty is a direct attack on Schmuck, who Leehrsen began doubting slightly and wound up holding in contempt by the time he’d fully dove into the Cobb story. The only deep dive Schmuck did in relation to Cobb, he writes, was raiding the back of the man’s liquor cabinet.

I’ve been wanting to get to this biography ever since I watched the entertaining-if-libelous Cobb movie starring Tommy Lee Jones, and am glad I finally got to dive into it. I already appreciated Cobb as a ballplayer, but Leehrsen’s research offered a view of a complex and interesting man, one who had his shortcomings but is inspirational in his obsession for excellence.

Cobb was learning something about himself that spring: […] he was the kind of person who would rather have the wind in his face than at his back. ‘I LIKE opposition’, he would observe years later. The many extra challenges he endure that spring and beyond seemed to help bolster his will and focus his mind. His great talent was not blocking out adversity, but letting it come through unfiltered and turning it into fuel. As Cobb’s historical figure, Napoleon Bonaparte,said:’Adversity is the midwife of genius.’ When Connie Mack once put it another way: ‘Don’t get Cobb mad.’ Anger made him better. [..] In this way he made his enemies, and his worries, complicit in his quest for greatness. Whatever did not kill Cobb would make him a .350 hitter — and in some years a .400 one.

Pingback: May 2025 In Review + Moviewatch | Reading Freely

Pingback: Top Ten Summer To-Reads | Reading Freely