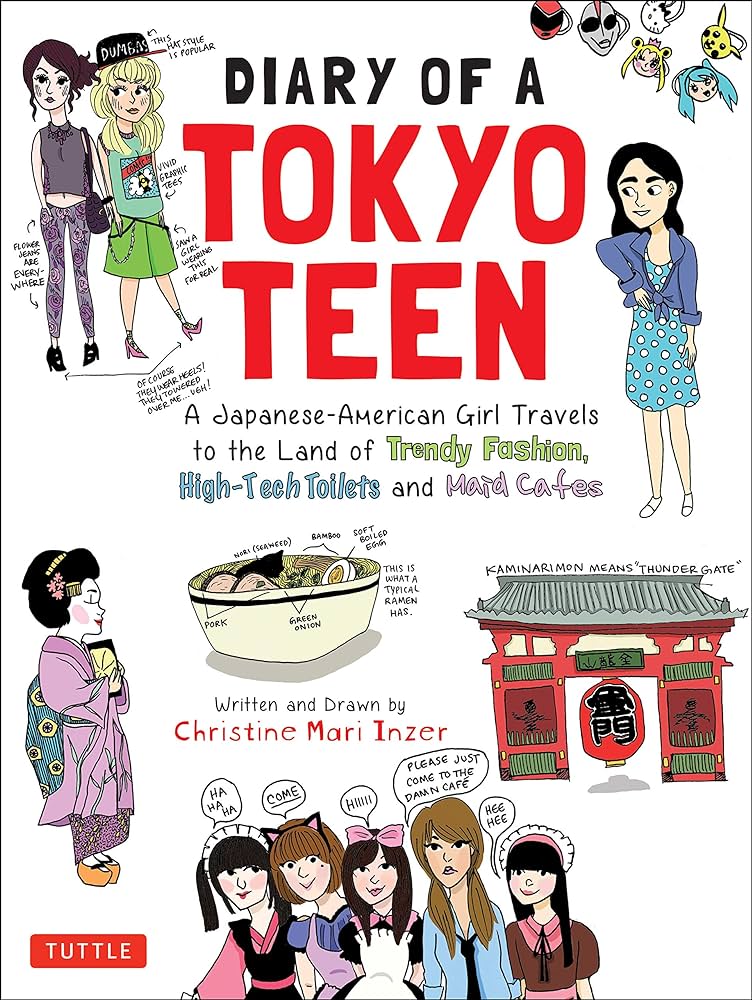

Diary of a Tokyo Teen is a graphic memoir of a Japanese-American teenager’s visit to her relatives in Japan, after an absence of five years. They live in an area not far from Tokyo, and the memoir covers her visiting various neighborhoods and sites around the prefecture, though she also uses the bullet train. Christine is half-Japanese, both by ethnicity and culture: she’s technically a Japanese citizen, but she’s so removed from Japanese life that she still gets to experience a fair bit of culture shock whenever she returns home and sees how things have changed. One of the running jokes is her discomfort with Japanese bidets, which use water for cleaning instead of wads of toilet paper. Unlike many in my generation, I missed the whole “Get obsessed with Japanese culture” thing (I enjoyed the Pokemon games in high school, and that was about it), so this year’s dips into contemporary Japanese life have been very interesting to me. There are also photographs included in the work, so I think it’s possibly inspired by a real-world trip she took back home. There was a lot of new content for me, like the Golden Pavilion, and I enjoyed the artwork.

The Science of Baseball takes a scientific look at the various material aspects of baseball — the creation of balls and bats, the maintenance of fields, the physics of fielding and hitting, the biomechanical stresses that various plays incur on the body — to see how they are at play in the game that so many love. There’s also a lot of sabermetrics, of course, and it gets a bit ‘inside baseball’ at times but not overly much so. I didn’t realize how much variability there was between baseballs and bats despite standarization, and that given batches could carry a performative biases — being more or less lively than a previous batch. This borders on inexplicable given the degree of standarization: the performance differences between different kinds of bats at least makes sense, given that fiber composition varies from wood to wood. There’s a large focus on how augmented reality tools are being used to closely study and coach pitching and batting, with some machines existing that can reproduce famous pitches from older games: the slugger who can afford one at home can theoretically practice against model pitches from all of the pitches he expects to see in the next season. Frankly the amount of computer modeling creeping in is unsettling, and I’m glad the MLB keeps a lot of tools off the field. Probably the most surprising fact in this is how obsessively cared-for ball fields are: mown and moisturized daily, and with genetically-modified grass and an array of different dirts and soils used for different parts of the field.

Highlights:

If somebody wants a perfectly predictable baseball, they’ll be better off playing MLB: The Show instead of watching actual ballgames.

Sonne isn’t just a scientist, but also a fan, who regularly says he grew up in the SkyDome (now Rogers Centre). I asked him what he notices when he first sees a pitcher and is it as a fan, or as a biomechanist? “The first thing that hits me every time I see an elite pitcher throw, is just how impressive the human body is,” he responded. “The internal rotation of the shoulder is one of the fastest movements in all of human motion, across any sport. As a kinesiologist, biomechanist, and fan of baseball, there isn’t a time that I watch a pitcher and am not blown away by how difficult, humbling, and beautiful the sport of baseball is.”Ol’ Hoss Radbourn, the pitching great of the late nineteenth century, would often tell the tale of the time he ended a game with a homer. It didn’t go over the fence—there was none—but instead went under a horse. One of the fans had just ridden up and when Radbourn’s hit went near it, it almost kicked the outfielder in his head! (Would that have been an error, or an assist for the horse?)

Even the grass is no longer a guess. There are several teams that model out how the ball will move in both the infield and outfield grass, which allows them to tailor it in the same way golf courses do for players. Want it a bit slower? That’s easy, just cut it this way and roll it to push the ball in. Want it faster? There’s an easy solution for that, with the field able to be kept at a very consistent “track” if they want it that way.

“I often get the question, ‘how can I get my high school field to look like Victory Field?’ My first question is, how much money do you have? You can have Victory Field without trained staff, but you need proper construction and engineering, draining, specific USGA sand, irrigation, engineered soil, and various clays and soils that come from all over the USA. Our infield is from Pennsylvania, our clay is from Iowa, our warning track is from New Jersey, our grass was grown specifically on sand in New Jersey from years of research and testing. Our indoor mound clay comes from Arizona and we have a crew of people who work seven days a week to keep this field in shape.

s