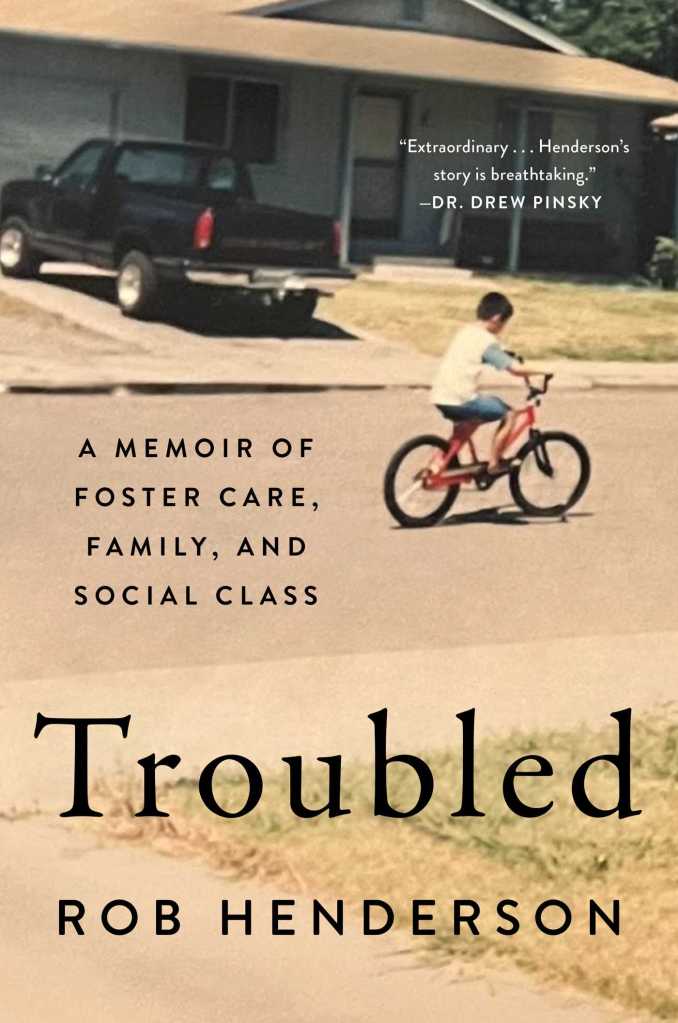

Imagine that your first memory is that of being three years old and seeing your mother, a drug addict who ties you to chairs to get high without interruption, being arrested. Imagine being bounced around ten different foster homes before you were driving age. That is Rob Kim Henderson’s story, of a boy born into absolute chaos who escapes falling into it through his own curiosity and the occasional positive influence of older adults who recognize some potential in him, who found stability and growth in an adoptive family and then the US Air Force. In many ways, this is a memoir similar to J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, in commenting on self-perpetuating cultures of poverty and social-moral chaos; both boys came of age amid violence, crime, and substance abuse, both found a guardian who offered them some stability despite the guardian’s own limits, and both ultimately found a way out of poverty and self-destructive behavior through the order and discipline that once marked the armed forces, culminating in educations at Yale. They differ, though, that Henderson not only reflects on the culture of poverty itself, but on how it’s effectively promoted by the luxury beliefs of the elites.

Troubled is, in large part, simply a memoir of a boy growing up in extremely adversarial circumstances and miraculously avoiding the worst consequences despite engaging in plenty of criminal and self-destructive behavior, behavior that would led his friends into prison or worse, death. It’s harrowing reading, as he was genuinely born into chaos: his mother was an immigrant from Korea who raised in in a car at one point, and his father is a complete unknown: the foster system was little better, as he was either one child among a dozen, raising one another in a feral sort of way, or used as menial labor. (He realized in retrospect that one family, the Martinez’, fostered young boys explicitly for that purpose: they never took in teenagers who would resist being turned into drudges.) As he neared his teen years, he was adopted by a young family who promptly fell apart after his mother fell in love with a woman, but who nevertheless gave him a modicum of stability. One of his peers told him he was lucky that his mother’s marriage ended that way: it meant his mother was never bringing home strange men who would abuse him, a fate that befalls too many foster and stepkids. Instead, she had a partner who was loving and supportive, even if she was suffering from her own gambling addiction. Although Henderson encountered a few men who offered him positive role models, like coaches, he writes that most of the male guidance he got came through literature: in fact, his curiosity about the world that led him to read was his salvation. There is also a slight role played by luck: the amount of instances where he could have been arrested for violent behavior alone is incredible, and his decision joining the Air Force and thereby developing more structure in his life that would take him out of poverty was almost impulsive.

What makes Troubled special, though, is the commentary that sometimes breaks through the surface of the narrative for most of the book, and is Henderson’s entire focus in the last chapters. Because Rob was a bright, inquisitive kid, when he left the culture of poverty behind him and went to places like the Air Force and Yale, he began comparing his life to those of his new colleagues — I can’t say peers, because he felt as though they were from different worlds. His reflection led him to realizing that stable family structure counted far more than mere income in setting the stage for a child’s life, and he asserts that public policy should be geared toward promoting families rather than making individuals more materially prosperous, and there’s an example in the book of a family receiving a windfall through an insurance settlement that ultimately goes to waste. A poor kid from a stable home can climb, but one reared in chaos will be lucky not to fall further — from basic psychological problems to the failure to develop skills for functioning in society. To his own experiences he adds in data from studies about kids from poor families versus kids from foster families that demonstrate how dramatically worse outcomes are for kids from broken families. Adding to this is his concept of ‘luxury beliefs’, which are beliefs espoused by the elite class because they’re politically fashionable, but which when applied in the lives of the poor, are utterly disastrous. He points out that the elites rarely practice what they preach, and when they do they do so in ways that shelter them from the worst consequences; it’s easy to talk about banning the police when you live in a safe neighborhood with security systems; when you’re a mother who has to worry about her kids being mugged by gangbangers on the way home from school, or still worse inducted into gangs, it’s altogether different While Henderson doesn’t delve into the public policy choices that incentivize socially ruinous decisions (like making it more profitable for a woman to have children from multiple fathers, rather than to be the baby-mama to one man, or even more radical, to marry a man and create a stable household), I can imagine him building on this. In the two weeks that I’ve known of his writing, I’ve enjoyed his articles and interviews enormously. We have now sunk as deep into the mire of the sexual revolution as we may go, I think — surely we cannot do worse than now, with Gen-Z seeming to give up on the enterprise altogether in a haze of SSRIs and porn — and it’s long past time for those most affected by it to begin lifting their voices in reproach.

Related:

The author’s substack, with articles like “Nobody Expects Young Men to Do Anything — and They Are Responding by Doing Nothing“.

Author interview with Michael Malice on “Your Welcome”.

Hillbilly Elegy, J.D. Vance

Pingback: The Best of 2024 – Year in Review! | Reading Freely