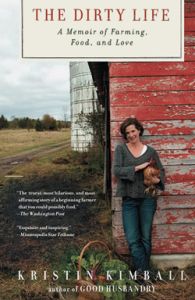

The Dirty Life: A Memoir of Farming, Food, and Love

© 2011 Kristin Kimball

287 pages

When Kristin Kimball left her cozy confines in the big city to interview a passionate young farmer in the sticks, she had no idea her life was about to change. Mark lived in a simple trailer and farmed someone else’s land, but he produced such exquisite vegetables that people came from miles around to buy food from him. His dream was his own farm, where he could go off-grid completely and develop something like a CSA on steroids – providing for the entirety of its members’ food needs. No sooner had Kristin showed up for the interview than Mark put her to work hoing broccoli. The two found themselves drawn together despite their differences in lifestyles, and before she knew it Kristin had left her apartment behind and pooled her money with Mark’s to engage in an enterprise of bringing a dormant farm back to life – learning not merely intensive gardening along the way, but animal husbandry and other diverse skills that farms demand at the most unexpected times. Most challenging, though, she and Mark both have to learn to be partners — pulling together as a team, much like their horses Sam and Silver.

The Dirty Life is, like the soil Mark and Kristin lived on, rich in value. On a superficial level, it’s the story of their first year trying to revive Essex Farm, which would have been challenging enough for anyone without the added burden of their ambition: they wanted to be able to provide a complete diet for not only them but dozens of others, which meant developing (quickly) the knowledge, stock and fields, and material infrastructure required to provide a diverse diet. They couldn’t just buy a few hundred head of cattle and send them off to be butchered: no, they were creating a wide range of animal products, and often developing the knowledge to do so on the fly. Mark was a master gardener, but neither he nor Kristin knew the first thing about animal husbandry — and now they were not only raising cows and swine, but driving horses. As Kristin quickly learned, knowing how to ride a horse is much different than working a team across the land.

All of this would be fascinating in itself, assuming you are interested in agriculture, homesteading, animals, local food, etc. But the soil keeps gets deeper, as Kristin continues to adapt to life on the farm. Previously, she’d lived a very comfortable existence as a consumer-creature, her life filled with ease, comfort, and pretty things. As a partner in Essex Farms, she worked long hours, abusing both her clothes and her body, and in addition to the daily demanding chores, she and Mark also had to navigate emergency after emergency. Despite frequently being sore and always being covered in dirt, blood, and…other stuff, though, the former comfy city girl found intense pleasure and meaning in this life of work, in the physical exertion itself and the satisfaction of seeing her labor immediately bear fruit. She and Mark also were not alone: from the moment they arrived in Essex, Mark and Kristin were welcomed into the local community, who were so glad to see new arrivals that they offered tools, advice, and labor freely. Like the Mendes in Better Off, and like the agricultural community portrayed in Wendell Berry’s Port William series, the Kimballs lived as members – most intimately with one another, and of their farm, but of the outside community. They saw and worked with the members of their village every day, and when they had developed to the point that offering shares was possible, the people of Essex were the first to buy in. By the first few years, they were feeding hundreds.

I knew I’d love this from the word go, and was not disappointed. Mark and Kristin recreated for themselves a life lost to most humans, a life not only wed to the land, within the rhythms of nature, but a life in full. Gone were Kristin’s days of sitting in front of a computer, using only her mind. The farm demanded mind and body — sometimes brute labor, but more often than not strength married to experience, strength guided by intelligence. They had to solve problems never anticipated, draw on inner reserves they never dreamt existed. Reclaiming the farm from neglect and abuse required every part of Mark and Kristin’s being: their muscles, their minds, and their spirits. They lived integrated lives, putting their whole selves to use but also integrating themselves into the community of Essex, where they became a vital part of its now-growing web of human connections. The more we descend into the brave new world of the 21st century, the more we drift from reality into some omnipresent digital construct, where we drift through as disembodied avatars with no more substance than a hologram cast in the sky, the more valuable perspectives like Kristin’s are. We hunger for substance and meaning, and she found both.

“Raw milk from a Jersey cow is a totally different substance from what I’d thought of as milk. If you do not own a cow or know someone who owns a cow, I must caution you to never try raw milk straight from the teat of a Jersey cow, because it would be cruel to taste it once and not have access to it again.”

“‘I don’t want to tell you what to do,’ Shep began. This, I’d found, was a very common statement in North Country. You’re not considered rude if you don’t return phone calls, or if you get drunk while working, or fail to show up as promised, but telling someone how to dosomething is bad form and requires a disclaimer.”

“As I patched the barn with scrap lumber, pig-tight but ugly, I was forced to confront my own prejudice. I’d come to the farm with the unarticulated belief that concrete things were for dumb people and abstract things were for smart people. I thought the physical world – -the trades — was the place you ended up if you weren’t bright or ambitious enough to handle a white-collar job. Did I think that a person with a genius for fixing engines, or for building, or for husbanding cows, was less brilliant than the person who writes ad copy or interprets the law?”

“This land had been farmed since before the American Revolution. The stock, the crops, the fence lines, the buildings, and the farmers had come and gone, passing over the fields like shadows in the course of the day. You can’t truly own a farm, no matter what the deed says. It has a life of its own. You can love it beyond measure, and you are responsible for it, but at most you’re married to it.”

Related:

Better Off: Flipping the Switch on Technology. Eric Bende. The story of a newlywed couple who join a ‘minimite’ community.

Literally anything by Wendell Berry, whose essays cover a lot of what Mark was concerned about, and who I would not be surprised to learn was an influence. The use of animals to work the farm instead of tractors, for instance.

Ditto Joel Salatin, who like Mark and Kristin took it on himself to reclaim a homestead that was not only abandoned, but largely ruined by machine-farming.

A wonderful review of a book that could be life-changing, I think.

This is the existence my 96-year-old dad relishes escaping from as a young man, but his memories of life on the farm are happy. I wonder if he might do things differently today and stay on the farm.

Kristin commented that when she talked to people raised on farms, they had one of two takes on it: either it was idyllic, or it was absolute drudgery. I imagine personality and the farm itself both go along way. Someone who is intensely social and adventurous would find the farm more tedious, for instance, and some steads are easier than others. My best friend grew up on a ranch that she still co-owns with her sister, and she loved growing up there and working with the cattle. I dogsit for her so I get to see a little of what goes into ranching, and her sister works LONG days — but she and her husband both wouldn’t do anything else. The worst season for them is calving season because cows respect no human schedules. Middle of the night during 20 degree weather? Tough!

Pingback: Farming for xp and fields | Reading Freely

Pingback: Midyear Review & June 2023 | Reading Freely